This Autumn, Carnegie Museum of Art presents work by nearly 60 Black photojournalists, who chronicled historic events and daily life in the USA from the end of WWII in 1945, through to 1984. This was a time of significant change, encompassing the civil rights movement, during which Black publishers and their staff created groundbreaking editorial, images and networks. The exhibition highlights titled like Afro American News, Pittsburgh Courier, Chicaco Defender and Ebony, which transformed how people were able to see themselves reflected, share news and build a community. The prints on display are drawn from archives in the care of journalists, libraries, museums, newspapers, photographers, with each one representing the energy of many dedicated individuals who worked to disseminate the news every day. Here, photojournalism is more than a job: it’s an act of resistance. Featured image-makers include Charles “Teenie” Harris, who made more than 75,000 images during his career, including portraits of jazz legends like Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong. There’s also John W. Mosley, who captured weddings, picnics, churches, sporting events, concerts and protests, and Moneta Sleet Jr., who is best-known for covering the life of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr and his family. Moreover, the show highlights Kwame Brathwaite, synonymous with the “Black is Beautiful” movement. Aesthetica spoke to the show’s curators, Dan Leers and Charlene Foggie-Barnett, about how these artists documented both historic occasions and quiet, domestic moments, bringing the fullness of Black life into focus.

A: Take us back to the beginning. How did this show come about?

DL: Carnegie Museum of Art is the repository for the Charles “Teenie” Harris Archive. He was an important photojournalist working for the Pittsburgh Courier between the 1930s and 1970s. Charlene is an expert on Teenie’s work, so we started to think about his place within a broader network of newspaper photographers and journalists. We were really trying to situate his practice within a continuum. It soon became clear that there was a community of people documenting subjects who were not being covered by other newspapers, whether because of disinterest or ignorance. Those photographers were part of a publishing network that, in many ways, was creating a new form of reporting that was much more community centred. Often they were telling positive stories, or, at least, they did not focus exclusively on the crime and violence that typically dominated media headlines about Black people in the USA. That was really where we started, travelling the country, going to different archives in libraries and museums, sometimes in people’s homes, and trying to paint a picture of this complex system.

A: Tell us about the curation process. What guided your decisions?

CFB: I got chills when Dan suggested the concept of this exhibition. I was honoured that he asked me to co-curate, because one of the aspects of my work is to make sure that communities – local, national and international – understand the impact of a photographer like Harris. I wanted to get across that these images were not made for art’s sake – although it’s also artistic in nature because it is beautiful photography – but in pursuit of visibility and to give proof of the Black experience. This is a show about how we actually lived, not the assumptions, misnomers or downtrodden stories. These are joyful, poignant moments, sometimes they might be a graduation or a rehearsal dinner for a wedding, or even just a child playing. We also wanted to foreground the role of women in this field, which is something that’s often overlooked but is a vital part of the archive. It’s important to remember that women were working in the areas that weren’t considered “high brow”, but appealed to the common reader. Some of the best information we have about Black life at this time comes from the society columns. These are just as interesting and valuable as something on the front page.

A: Photojournalism is often seen as objective, but as this show reveals, it’s also deeply personal. How did you reflect this in your curation?

CFB: I was one of the everyday people photographed by Charles “Teenie” Harris, from infancy through into my 20s. My parents were civil rights leaders here in Pittsburgh, and my mom had grown up with Teenie. This meant that I got to see his process, I witnesses him carrying this heavy equipment all over the place. You never saw him without a camera. It was the same for many of the people doing this, it was a 24/7, 365 job. It wasn’t just a question of whether a shot was newspaper worthy, it was also important that I got my birthday party picture, or my parent’s wedding anniversary was captured. These are the moments you don’t see in traditional press, but at the same time, the subjects of these ordinary moments could be extraordinary people, like Pulitzer Prize winners, a cotillion queen or a community leader. There’s a real marriage of the iconic and the everyday.

A: The description of the show says “photojournalism is craft and documentation.” How did you balance historic representation with artistic presentation?

DL: We’re very fortunate that many of the photographers in this exhibition are still alive, and we’ve been able to have conversations with them. Many of them say “I wasn’t a photojournalist.” Every photographer had to earn a living, oftentimes alongside what you’d refer to as more artistic pursuits. I’m thinking, in this case, of people like the MNA Group in New York City. They were committed to making their photographs, showing them in galleries and museums and talking about them with fellow artists. But they also had to pay the bills, so they were taking assignments from Sports Illustrated. There were people, such as Gordon Parks, who had a role as a staff photographer, but these were rare. What we tried to do as we put together the exhibition, which meant whittling down thousands of pictures to just a few hundred, was to select works that represented all aspects of this range. We asked: which pictures stand up as compositionally interesting and are going to be compelling to look at? Sometimes these pictures were made on assignment, sometimes they weren’t, we just tried to make the most interesting show we could.

CFB: I think the blend of having Dan as a photographic expert was vital. He not only has a great knowledge of history, and Black history in particular, but from a photography standpoint, he also taught me a lot about what makes a great image. This worked really well alongside my lived experience. I grew up during the civil rights movements. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, alongside other influential people like Jesse Jackson, were in my home to meet my parents and work as part of the campaign trail. I think the blend of mine and Dan’s backgrounds and knowledge made the curation process very rich. Every time we looked at a picture together, we would come at it from our different perspectives, but I would always learn something. I think our hope is that in this exhibition, the same thing will happen. Everyone will bring their own viewpoint to it. None of them are wrong, they’re all unique and can help piece together a new and unique story.

A: The exhibition spans from 1945 to 1984. How does this specific time frame help us understand the political and cultural shifts captured in the photographs?

DL: We start with the end of WWII in 1945 because there was a real push on the part of the Black community to have a broader coverage of stories. You had Black service members coming home from overseas and saying “I’ve just fought for the freedom of people living in Europe and I’m coming home to a racist and segregated society. That’s not right.” As a response, you had papers like the Pittsburgh Courier, which in the 1940s reached over 300,000 subscribers. These were truly national publications, starting things like the “Double V” campaign, which signified a desire for victory over the enemy abroad and over discrimination at home. You also had a boom in new publishers coming to the market, like Ebony Magazine, which arrived in 1945, followed by Jet in 1951. You also had the NNPA, the National Negro Publishers Association, now called the National Newspaper Publishers Association, coming together as a sort of trade group. Langston Hughes was writing for the Chicago Defender, another widely circulated newspaper, so there’s this explosion in coverage and a hunger for stories that carries through into the 1950s and, of course, the 1960s with the civil rights movement. We continue into the 1980s because its around this time that digital publishing starts to come into the mix and that really changes photography and photojournalism. That’s one reason that we stopped there, but the other is that we wanted to end on a note of optimism and for us, the Jesse Jackson presidential campaign in 1988, when he ran on the slogan “Keep Hope Alive”, felt like the right point.

A: What can we learn from these photographers?

CFB: These practitioners are offering us proof of the Black experience in the USA. It is ingrained in our culture that you start with slavery and a downtrodden story, moving through poverty and lynchings, to the civil rights movement before arriving at today. We have heard that again and again, and its important history, but we’re not those experiences, the same way we are not all the Obamas or Jay-Z and Beyonce either. Most of us African Americans live, and have always lived, in a middle ground. It is these situations that photojournalists are sharing, and it’s not common knowledge. When I show guests what we have in our archive, like tea sets, nice clothes or cars, people are often shocked. Until we prove that middle ground existed, we aren’t really telling the whole story. Young people need to understand why it’s important to carry this history, or it’ll be lost. If that happens, especially in the USA Today, who knows what’ll happen.

DL: It’s also increasingly uncommon that people still know what it took to produce a picture before digital. These people were carrying two, even three, cameras with them, maybe one for black-and-white and one for colour film. They were also taking their film with them everywhere. As soon as they exposed it, they had to race home to develop it in their basement or darkrooms. They were printing the image, sometimes making multiple versions, and then sending it to different papers around the country. This was a tremendous effort. You didn’t take a photo if you didn’t think it was worth it because it took a lot of time and money. It’s important to remember the level of care and dedication each shot took. There’s also the labour that went into making the newspapers, the editors and the proofreaders and publishers all had to work together to bring these experiences to light.

A: Do you each have a particular favourite image, artist or story in the show?

CFB: Well, for me, of course, it’s Charles “Teenie” Harris because I know that archive so well. But I also have to say the story of Las Vegas, Nevada, is a personal favourite of mine. When you think of Las Vegas, you don’t necessarily think it was a hotbed of civil rights, but Clinton Wright photographed in the area, and through his work, the discrimination in casinos and local areas was made known. There were clearly delineated neighbourhoods that African Americans had to live in. Even the top performers, those who were headlining on the strip, couldn’t stay in the hotel where they worked and had to go out to these barracks. Another aspect that really clicked with me is Sistagraphy. They’re a group of women of colour in Atlanta, Georgia, who come together to exhibit their work around the country. We were so excited to learn about and meet with them, so those two stand out the most.

DL: One thing to say is that we didn’t discover these pictures, they’ve been known about by communities, archivists and librarians since the moment they were taken, we’re just sharing them with a new audience. One story that really moved me was the Baltimore Afro-American, it’s a paper that was started in the 1980s by John H. Murphy, with funding from his wife. The publication has had a long tradition of women playing important roles, whether it was the first Black overseas war correspondent, or the first Black sports reporter, it was an incredibly diverse and democratic workspace. Today, a woman called Savannah Wood has dedicated herself to digitising and making accessible more than 2 million artefacts in the Baltimore Afro-American’s archives. It’s an incredible testament to the role that women play, but also just how personal and familial this history can be. We have pictures from the Afro-American in the exhibition, as well of a number of actual copies of the paper. I love thinking about that history as I look at the material and knowing that there are still young people committed to this legacy.

A: What do you hope visitors take away from the exhibition?

DL: I’d like them to gain fresh knowledge, whether it’s new to them entirely or a different side of what they already know. I want people to see something unique. We have a photo of Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks leaning against a fence, perhaps waiting for a public event. It’s this everyday experience of iconic people that I aimed to get across. I hope people take away the bits they don’t always see.

CFB: My sentiment is similar – I want people to understand that everyone has a unique perspective and a story to tell, and that if we share these collectively, they have the power to change the world. My truly grandiose hope is that guests, and especially young people, come out of this exhibition understanding that the pictures they take can really say something about who they are and the circumstances in which they live. I hope it inspires a certain level of intentionality and openness on the part of people taking and sharing photographs, so that we can find space for all those perspectives in the history that we are now making.

Black Photojournalism is at Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh until 19 January: carnegieart.org

Words: Emma Jacob

Image Credits:

1. Kwame Brathwaite, born 1938, New York, NY; died 2023, New York, NY; Changing Times, ca. 1973, printed 2025, inkjet print, 15 _ 15 in. (38.1 _ 38.1cm); The Kwame Brathwaite Archive; Kwame Brathwaite.

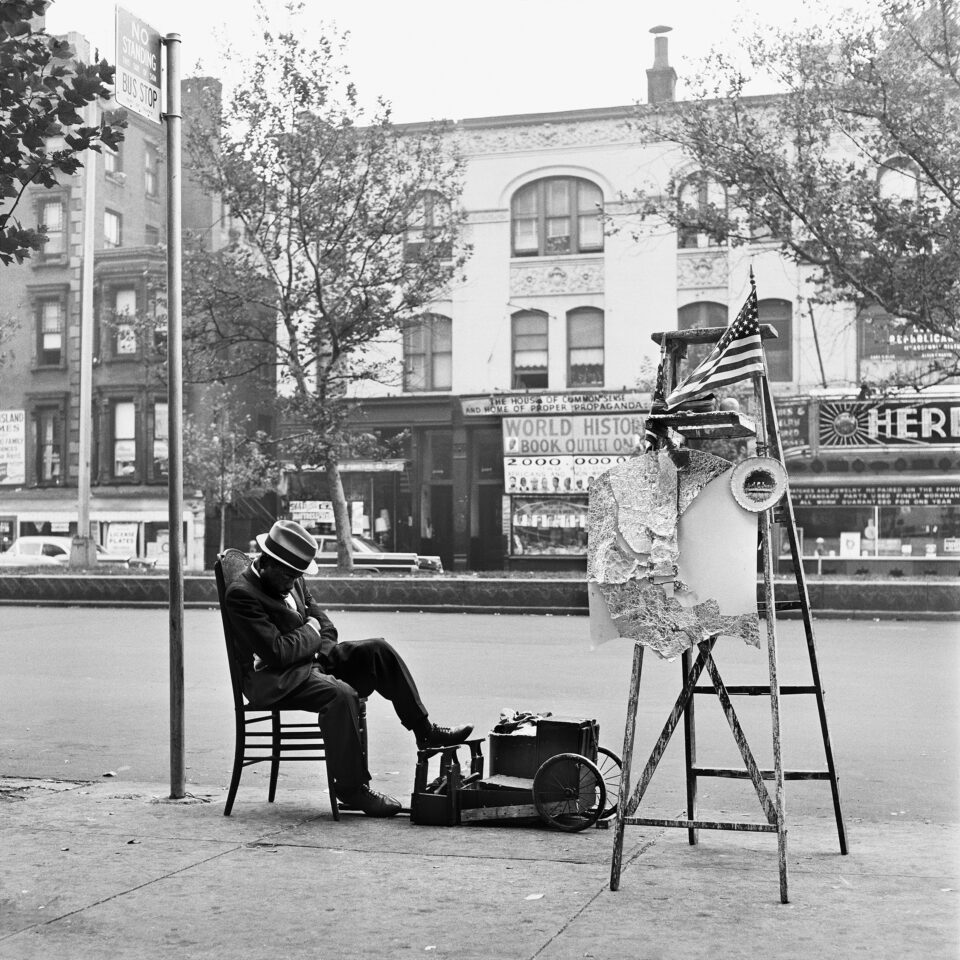

2. Kwame Brathwaite, born 1938, New York, NY; died 2023, New York, NY; Michauxs Books, ca. 1964, printed 2025, inkjet print, 15 _ 15 in. (38.1 _ 38.1 cm); The Kwame Brathwaite Archive; Kwame Brathwaite.

3. Kwame Brathwaite, born 1938, New York, NY; died 2023, New York, NY; Jacksons on Boat from Goree Island, ca. 1974, printed 2025, inkjet print, 30 _ 40 in. (76.2 _ 101.6 cm); The Kwame Brathwaite Archive; Kwame Brathwaite.

4. Bob Douglas, born 1921, Detroit, MI; died 2002, Los Angeles, CA; Dizzy Gillespie, ca. 1963, printed 2025, inkjet print, 8 x 10 in. (20.3 x 25.4 cm); Tom & Ethel Bradley Center, California State University, Northridge, University Library; photo: Courtesy of the Tom & Ethel Bradley Center at California State University, Northridge.

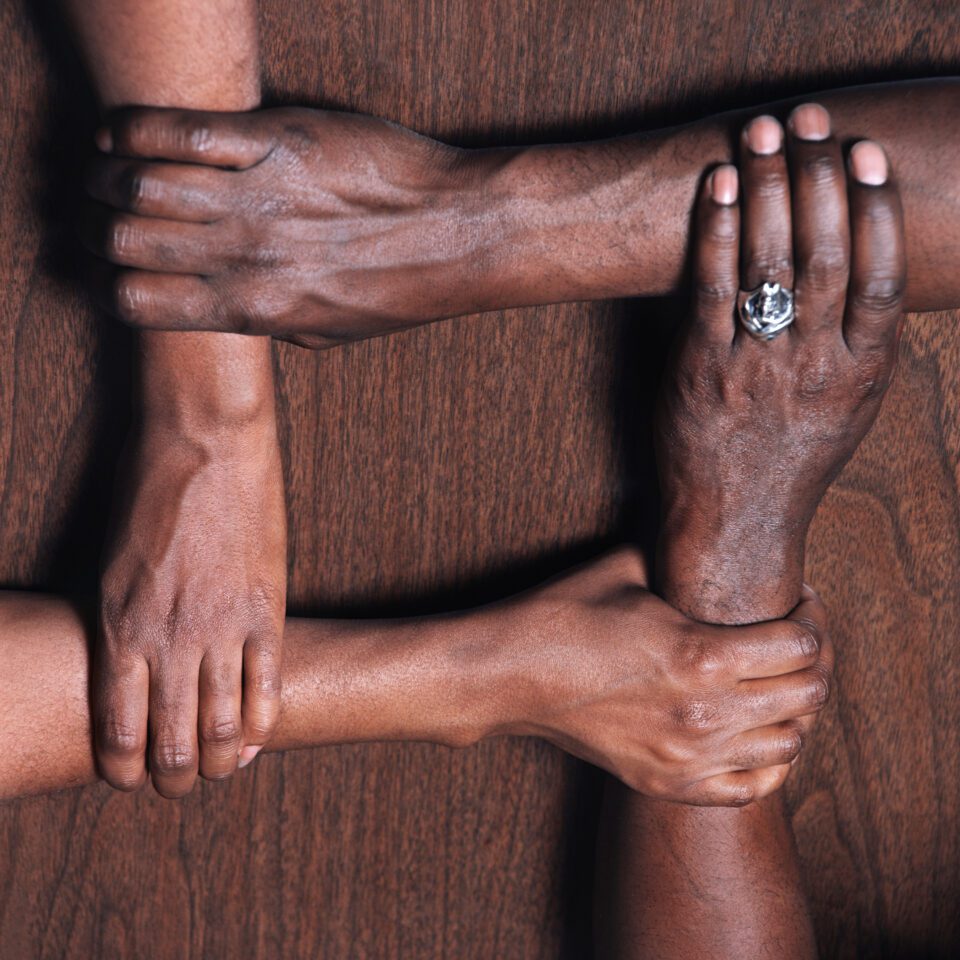

5. Kwame Brathwaite, born 1938, New York, NY; died 2023, New York, NY; Untitled (hands in the shape of a Unity symbol), ca. 1971, printed 2021, inkjet print, 29 _ x 29 _ in. (75 x 75 cm); Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, Purchased with funds provided by Dawn and Chris Fleischner, 2022.7; _ Estate of Kwame Brathwaite.