Gordon Parks understood the camera as a weapon, a tool for justice and revelation. Born in 1912 in Fort Scott, Kansas, he transformed the lens into an instrument capable of exposing both brutality and beauty, inequality and resilience. His photographs chronicled the daily lives, struggles and triumphs of Black Americans, insisting that their stories be seen and remembered. We Shall Not Be Moved, now at Alison Jacques in London, presents these works in a powerful dialogue with the present, reflecting Parks’ capacity to bear witness while demanding accountability. The exhibition coincides with the 20th anniversary of The Gordon Parks Foundation, celebrating a legacy that continues to shape contemporary photography. Peter W. Kunhardt, Jr., Executive Director of the Foundation, states: “We are pleased to celebrate The Gordon Parks Foundation’s 20th anniversary with an exhibition at Alison Jacques in London. We are equally fortunate to view Gordon’s vast achievements through the critical lens of guest curator Bryan Stevenson.”

Bryan Stevenson brings a deeply personal perspective to this curation. Founder and Executive Director of the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama, Stevenson has received the Martin Luther King Jr. Nonviolent Peace Prize (2018) and was named in Time100: World’s Most Influential People (2015). He is also the author of the critically acclaimed Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption (2015), awarded the Carnegie Medal and adapted into a major HBO film starring Michael B. Jordan (2019). Stevenson observes that “the scope of the images from Parks represents the struggle, resilience and constant striving of Black Americans.” His selection spans 25 years of Parks’ practice, from 1942 to 1967, portraying him as a humanitarian whose art and activism were inseparable. By highlighting race, class and systemic inequality, Stevenson ensures the exhibition speaks as urgently to contemporary audiences as it does to history.

From the beginning, Parks approached photography with determination and vision. In 1937, he purchased a Voigtländer Brillant camera from a pawnshop for under £12, inspired by photographs of migrant workers. He described his camera as a “weapon” against social injustice, stating: “You have a 45mm automatic pistol on your lap, and I have a 35mm camera on my lap, and my weapon is just as powerful as yours.” His early work for Life magazine broke barriers when he became its first Black staff photographer in 1948, and he often wrote his own articles, allowing him to shape the narrative as he captured it. Parks’ photographs combine artistry with empathy, portraying subjects with dignity and depth rather than through reductive stereotypes. The exhibition emphasises the enduring precision and ethical clarity of his practice.

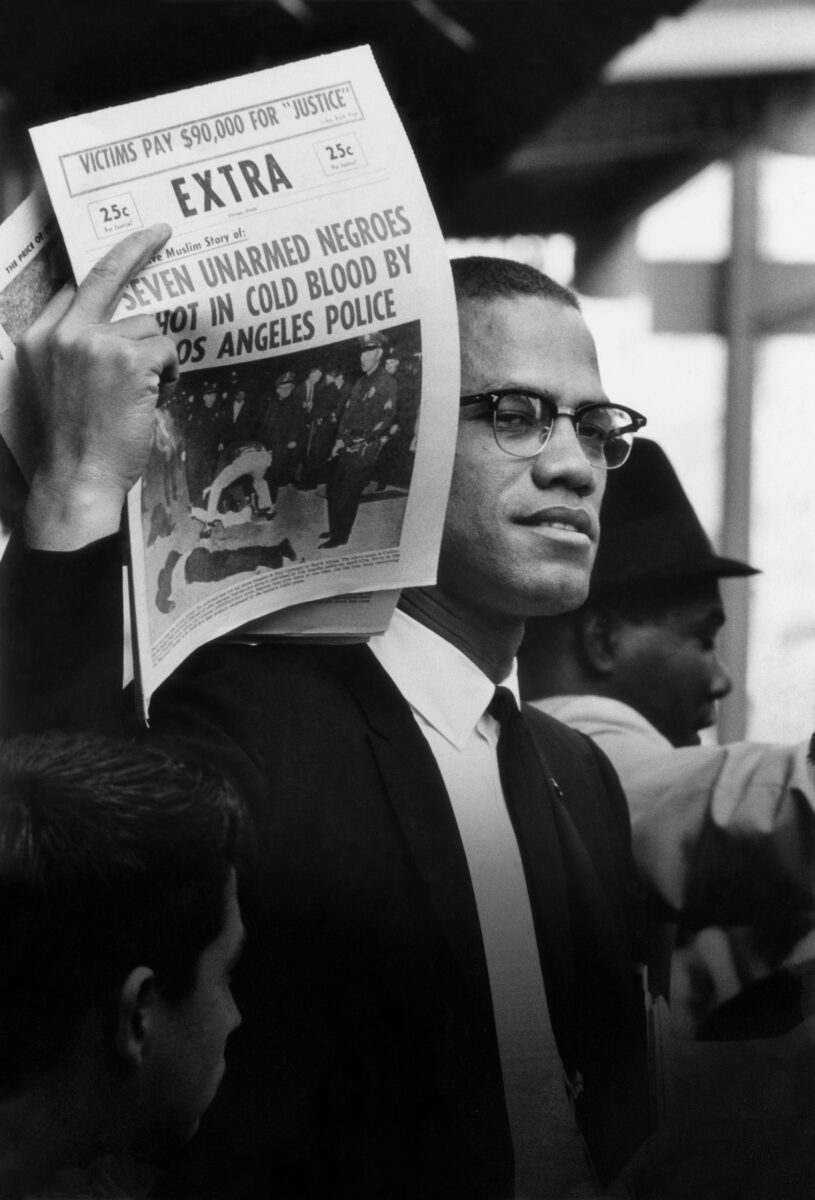

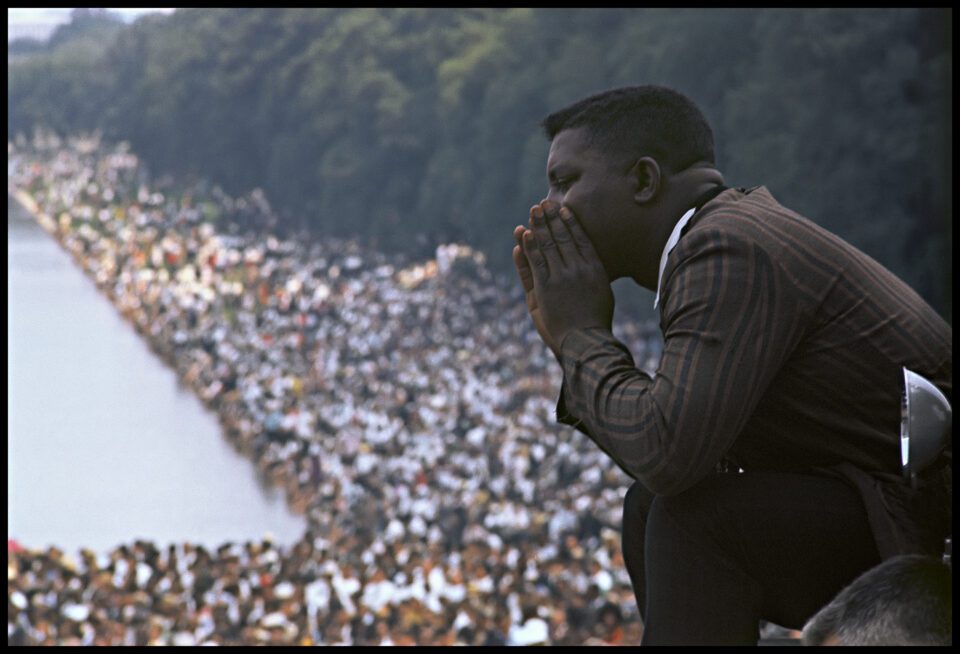

Parks’ Segregation in the South series, including Outside Looking In, Department Store and Mr and Mrs Albert Thornton, remains a cornerstone of documentary photography. Commissioned by Life and published as The Restraints: Open and Hidden (1956), the series follows Black family life in Alabama, revealing routines shaped by systemic restrictions alongside moments of everyday joy. His portraits of Dr Martin Luther King Jr. at the March on Washington and other figures assert the humanity of their subjects with quiet insistence. Stevenson notes that Parks’ personal experience as an African American survivor of injustice “palpably informed his work,” giving the photographs their distinctive compassion and authority. These images challenge viewers to confront the realities of Jim Crow through a lens of recognition and empathy.

In his Atmosphere of Crime series (1967), Parks turned his attention to urban life and the structures of incarceration. Photographs such as Untitled, Chicago, showing a prisoner’s hand extending from the bars of a cell with a cigarette, humanise experiences often reduced to statistics. Stevenson’s essay The Lens of Gordon Parks: A Different Picture of Crime in America (2020) illustrates how Parks reframed narratives around criminality, focusing on systemic causes rather than personal blame. The exhibition pairs these later works with earlier portraits, highlighting the consistency of Parks’ concern for dignity and justice. His photography balances aesthetic refinement with moral urgency, demanding attention and reflection.

Artists working today continue to respond to Parks’ vision, extending his engagement with race, identity and social critique. Deana Lawson’s staged family portraits echo Parks’ intimacy and attention to domestic life. Carrie Mae Weems interrogates historical memory and identity, employing photography to explore Black experience with the same ethical acuity Parks modelled. LaToya Ruby Frazier documents communities affected by industrial decline and neglect, reflecting Parks’ interest in the environmental and social conditions shaping human life. Together, their work demonstrates the enduring influence of Parks’ approach, revealing how he created space for nuanced, socially aware storytelling.

The exhibition presents iconic images such as American Gothic, Washington, D.C. alongside lesser-known works, establishing a dialogue between the monumental and the everyday. Parks’ mastery of light, composition and gesture renders each frame both visually compelling and morally resonant. The gallery layout emphasises continuity across decades, from segregated towns of the 1950s to urban landscapes of the 1960s, highlighting the persistence of the social issues he confronted. The exhibition situates Parks as both witness and participant, showing photography’s capacity to illuminate, challenge and inspire.

Gordon Parks: We Shall Not Be Moved affirms his status as one of the most significant photographers of the 20th century. By centring his commitment to human dignity, the exhibition draws attention to the ongoing relevance of his work. Each photograph functions as an invitation to bear witness, urging audiences to see as Parks did: with focus, empathy and insistence on justice. The 20th anniversary of The Gordon Parks Foundation reinforces the importance of preserving this legacy while celebrating its continuing influence. Through the exhibition, Parks reminds us that photography is a tool for understanding, advocacy and hope.

Gordon Parks: We Shall Not Be Moved is at Alison Jacques, London 5 March – 11 April: alisonjacques.com

Words: Simon Cartwright

Image Credits:

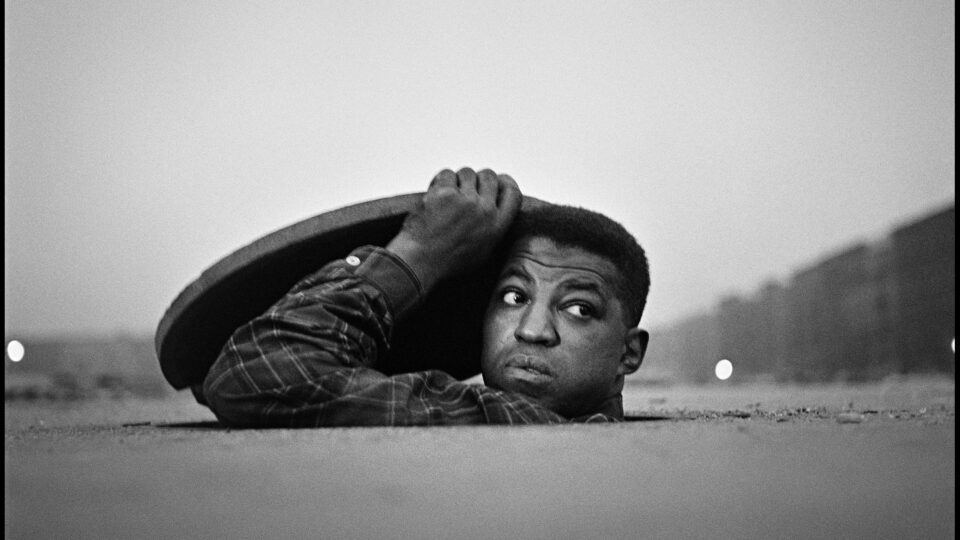

1. Gordon Parks, The Invisible Man, Harlem, New York, 1952, Silver gelatin print, 86 x 86 cm.

2. Gordon Parks, Outside Looking In, Mobile, Alabama, 1956, Archival pigment print, 163 x 163 cm.

3. Gordon Parks, Man with Straw Hat, Washington, D.C., 1942, Silver gelatin print 61 x 51 cm

4. Gordon Parks, Department Store, Mobile, Alabama, 1956, Archival pigment print, 163 x 163 cm.

5. Gordon Parks, Uncle James Parks, Fort Scott, Kansas, 1950, Silver gelatin print, 36 x 28 cm.

6. Gordon Parks, Untitled, Shady Grove, Alabama, 1956, Archival pigment print, 163 x 163 cm.

7. Gordon Parks, Malcolm X Holding Up Black Muslim Newspaper, Chicago, Illinois, 1963, Gelatin silver print, 51 x 41 cm.

8. Gordon Parks, Untitled, Washington, D.C., 1963, Archival pigment print 61 x 76.2 cm.