Photography, like memory, is always partial. Female. Focus. Photo Archives., opening at Fotostiftung Schweiz this February, makes this truth tangible. For over a century, Swiss photography has been narrated through male eyes while the achievements of women remain largely invisible. Of approximately 160 archives held by Fotostiftung Schweiz, only 26 belong to women, a stark reminder of systemic bias and selective preservation. The exhibition examines seven archives from 1900 to 1970, exploring how gender, social expectation and circumstance shaped practice, recognition and visibility. It interrogates who was allowed to photograph and whose images were deemed worthy of remembrance.

Anny Wild-Siber (1865–1942) occupies the space between amateur and innovator. Her archive reveals mastery of early colour processes such as Autochrome and Uvachrome alongside pictorialist printing techniques that transform landscapes and still lifes into art objects. She submitted work to international competitions and photo salons, asserting a presence in spaces usually dominated by men. Yet her archive also hints at private experiments and ephemeral images never exhibited, emphasising the tension between public and private creativity. These photographs pulse with curiosity and careful composition, demonstrating that amateur status did not preclude ambition or artistic vision. Wild-Siber’s work quietly asserts that technical skill and aesthetic sensibility were not gendered qualities but human ones.

Wealth and autonomy defined Gertrud Dübi-Müller (1888–1980), whose photographic practice intertwined with her position as collector and patron. She captured artists such as Ferdinand Hodler and Cuno Amiet, documenting both creative labour and the social milieu surrounding it. Using a stereo camera, she also recorded mountain hikes, society life and military deployments along the Swiss border in 1914, blending monumental history with everyday observation. Her archive conveys both privilege and attentiveness, highlighting how access shaped opportunity and legacy. Dübi-Müller’s work demonstrates the ways social standing intersects with visibility, preserving images that might otherwise have been ignored. In this, the archive becomes both an artistic statement and a document of her era.

Marie Ottomann-Rothacher (1916–2002) exemplifies the balancing act many women navigated between professional ambition and domestic responsibility. Trained in the studios of Heiri Steiner and Ernst A. Heiniger, she spent weekdays in studio work and weekends producing reportage for Pro Juventute while also documenting her family life. From 1957 onwards, she moved between various studios, reflecting a career marked by both continuity and fragmentation. Her archive captures this duality, containing both polished professional images and intimate personal moments. It demonstrates how women’s photographic practice often encompassed multiple spheres of life simultaneously. In these layered records, the archive becomes a mirror of lived experience, revealing both artistry and circumstance.

Margrit Aschwanden (1913–2004) inherited photography as a family vocation in the Canton of Uri. She apprenticed with her brother, passed the master’s examination at ETH Zurich and later documented children’s homes for the Swiss Red Cross before opening a studio with her sister in Flüelen. Her archive combines technical mastery with a commitment to social consciousness, reflecting both personal skill and familial lineage. Yet gaps remain: the contributions of assistants, collaborators and clients are largely absent, reminding viewers that archives are always selective. Aschwanden’s work demonstrates how family, profession and social responsibility intertwined to shape visibility. The archive becomes both an aesthetic record and a testament to the conditions under which women produced their work.

Hedy Bumbacher (1912–1992) approached photography with the mind of a scholar, drawing on her studies in history, psychology and biology. She trained at ETH Zurich and freelanced for Pro Juventute, photographing Swiss mountain villages and producing images for farming subsidy campaigns and the Berghilfe mountain aid organisation. Her archive embodies rigorous observation and compositional precision yet also gestures toward absence: the broader social networks and unpublished negatives remain largely unseen. Bumbacher’s images balance documentary intent with aesthetic care, revealing the complex intersections of technical skill, research and empathy. They demonstrate how archival presence can coexist with gaps, creating space for reflection on both inclusion and omission. Her work exemplifies how archives document not only what is visible but what is valued.

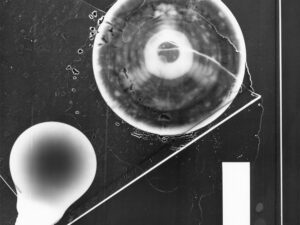

Leni Willimann-Thöni (1918–2002) explored collaboration, authorship and recognition. After training at the Zurich School of Arts and Crafts, she worked alongside her husband Alfred Willimann on Muscheln: Ein Wegweiser zu ungeahnten Sammlerfreuden (1960), producing photographs guided by the New Objectivity style. The archive preserves formal precision and compositional clarity yet it also raises questions about attribution. How often were women’s contributions subsumed under collective or male authorship? Willimann-Thöni’s work demonstrates how archives can reveal both skill and structural inequity, offering a lens through which to reconsider the conditions of production. Her images maintain quiet authority, asserting presence even where historical recognition has been muted.

Anita Niesz (1925–2013) placed human connection at the centre of her photographic practice. After studying at the Zurich School of Arts and Crafts, she published photojournalistic reports in Du from 1949, working with Swiss Refugee Aid and Pro Infirmis. Her archive is rich with portraits and reportage, documenting everyday dignity and social encounters. Yet it also gestures to what is missing: the unpublished images, editorial choices and unseen participants who shaped her work. Niesz’s photographs exemplify empathy and engagement while highlighting the selective lens of history. In this archive, presence and absence coexist, inviting viewers to reflect on how recognition is assigned.

Taken together, these seven archives illuminate photography as both vocation and negotiation. They ask: “To what extent was photography a female profession? How did prevailing role models, economic structures and family duties impact the work of women photographers and the recognition they received?” Each archive tells a distinct story yet collectively they highlight systemic inequities in opportunity and legacy. Gaps in the collections are as instructive as what has been preserved, prompting reflection on the biases that have historically shaped cultural memory. The exhibition turns absence into dialogue and shadow into substance. It encourages viewers to reconsider history and archival authority.

Female. Focus. Photo Archives. reframes archives as sites of enquiry, not passive storage. The curators emphasise the conditions of production alongside the images themselves, showing how photographs are shaped by access, opportunity and social hierarchies. The exhibition restores shadows to visibility, challenging assumptions about authorship, legacy and value. It demonstrates that photographs are not neutral records but active agents in shaping cultural memory. By examining both what is present and what is absent, the exhibition highlights how selective archival practices influence how history is remembered. The archive becomes a space of critical reflection as well as aesthetic engagement.

Ultimately, the exhibition inhabits the tension between presence and absence. Photographs become witnesses to both resilience and inequity, documenting what was created and what was left behind. Archives are transformed into dialogues, revealing the structures that dictated visibility while celebrating the women who navigated them. Each image is both record and revelation, asserting creativity, skill and humanity. Female. Focus. Photo Archives. invites reflection on history as a living conversation, where omissions are as instructive as what has survived. In foregrounding female vision, the exhibition reclaims photography itself as a terrain of possibility, curiosity and enduring beauty.

Female. Focus. Photo Archives. is at Fotostiftung Schweiz, Winterthur from 28 February: fotostiftung.ch

Words: Simon Cartwright

Image Credits:

1&6. Elisabeth Brühlmann, Marie Ottomann-Rothacher working in the atelier of Hans Peter Klauser, Zurich, 1960 © Elisabeth Brühlmann Sarlo / Fotostiftung Schweiz.

2. Leni Willimann, Mussels (Isocardia cor), 1960 © Leni Willimann / Fotostiftung Schweiz.

3. Andri Pol, flight demonstration by the Patrouille Suisse aerobatic team, Army Days in Frauenfeld, Canton of Thurgau, Switzerland, 1998 © Andri Pol.

4. Anita Niesz, Troyes, France, around 1955 © Anita Niesz / Fotostiftung Schweiz

5. Andri Pol, Silvesterchlaus in the Urnäsch area, Canton of Appenzell Ausserrhoden, Switzerland, 2005 © Andri Pol.