Eileen Perrier (b. 1974) first took up the camera in the 1990s, and has steadily documented London, its people, places and diasporic communities ever since. Born and raised in the city, Perrier often found herself caught between her upbringing and her dual Ghanaian and Dominican heritage. The sense of ambiguity this brings is central to her work, examining how identity is shaped by both geographical and cultural context. She uses portraiture to forge connections between people, acknowledging the profound value of being seen. Her images employ the tropes of 19th century European and contemporary African studio portraiture to contemplate how class and belonging are represented. The artist is also a senior lecturer in photography, influencing the next generation of creatives. A Thousand Small Stories, the first retrospective of the artist, is now on display at Autograph, London. The show brings together three decades of photographs, from gentle explorations of kinship and memory to a lively community beauty salon in Brixton. Aestheticaspoke to Perrier about her career, how a trip to Ghana influenced her creative trajectory and the ways the photographic landscape has changed over the past three decades.

A: Where did your involvement with photography begin?

EP: One of my first encounters with the camera, and the moment I became really excited about it, was when I started my A-Levels. I’d originally taken physics, chemistry and biology, but realised they weren’t working for me, so I took up photography and instantly loved it. I had that “aha” moment when working in the dark room, and great teacher called Trevor Parslow-Williams, so that was where I got the bug. From there, I went on to do my degree at the University for the Creative Arts in Farnham, specialising in documentary photography. The lecturers there were incredible, people like Anna Fox, Martin Parr, David Bates, David Moore and Peter Kennard. They were practicing as well as teaching, which was amazing. Around the same time, I came across a book by British-Jamaican artist and photographer Armet Francis and I loved his portraits. I met him by chance one day, we stayed in touch and he became a mentor to me. Anna Fox was also really supportive of my work while I was at UCA, so once I graduated, she encouraged me to get in touch with Autograph. They commissioned me to develop the Red Gold and Green (1997) series, which I started working on after I visited Ghana in 1995 and was a real turning point in my career.

A: You mentioned that your visit to Ghana was a pivotal moment. How did that experience shape your perspective on photography?

EP: I knew whilst studying documentary photography that I wanted to focus on a subject that was personal and important to me. My Mum first moved to the UK from Ghana when she married her first husband at 19, and hadn’t been back since. That relationship ended, and he decided to go back but she stayed here, despite lots of people saying she should travel back to Ghana to see her family. She never did, and as I got older, I became more interested in what “going back home” meant. My dad is from the West Indies, and I’d have people ask me: have you been to Ghana? Have you ever gone back to Dominica? And when I said no, it really prompted me to question where I fit, and to know more about my family roots. So, I used my student loan to pay for me and my mum to fly out to Ghana. I didn’t know what to expect, I just knew that I wanted to photograph everything that I saw – people, places, the rooms we were staying in. People did speak English, but it was more common to hear them speaking in their mother tongue so there was a lot of times when I was just observing, which really informed how I took my photographs.

A: How do you incorporate a sense of spontaneity into your creative practice?

EP: I often take pictures on my mobile phone, because it’s something easy to carry that I’ll always have with me and prior to that I used to use a compact film camera. I will take a picture, even if it’s just to document the idea, and then return to that location with my camera. For a few years, I did a whole series of images called Mobile Phone Portraits, which stemmed from being in the park, seeing a family and thinking “they look interesting visually.” There was a grandmother holding a baby and then a women I think was the baby’s mother, as well as two young boys, one of which looks up from his Nintendo DS. The scene was touching, and I asked if I could take a picture of them because I didn’t want to let that moment pass me by.

A: You worked with your own family in Red, Gold and Green, to create portraits in their London homes. What was it like to collaborate with your relatives on a project?

EP: During the trip to Ghana, it hit me how important my mum’s friends were to her back in London. They were her family. I thought, okay, I need to document the people we consider family, because they’ve been integral to my mum’s life. I couldn’t ask them to come to the university in Farnham to be photographed, so I came up with the concept of taking the studio to them. I’d take lights and backdrops and set them up in people’s homes. I also decided to use red, gold and green, which are the colours of the Ghanaian flag.

A: Talk us through A Thousand Small Stories. What was the process of looking back at your career and putting the show together?

EP: Bindi Vora, the curator of the show, is a former student of mine from the University of Westminster. It’s been an interesting process having her curate this exhibition. She has come to my home a few times, as I don’t have a studio, to go through my work and make an inventory. Some of those works have been stored in cupboards for years, so it was strangely emotional to take it all out and go through it. A Thousand Small Stories is just a snippet of my photographic archive. I could fill three or four more rooms, so it was fascinating to see the process of curation and watch Bindi decide which are the key moments she wanted to pull out for the exhibition.

A: The show opens with When am I gonna stop being wise beyond my years?, which addresses the realities teenage girls face while grappling with social media, body image and misogyny. Has social media and technology changed how you see portraiture?

EP: That project was commissioned by Face Magazine, and came about after the editor saw my work in an exhibition at Somerset House. It was an honour to be noticed by them, so many years after I first became familiar with their work in my teens and early 20s. In terms of how social media and technology has shaped photography, it’s a big question. A lot of my work is focused on identity, and you can see how people view themselves differently these days due to social media. If anything, we’re oversaturated with images now and its quite overwhelming. People take selfies all the time, and it’s interesting to see how everyone having a phone in their pocket has changed the world. It’s a great equaliser, and even to think about things like the murder of George Floyd in 2020, the use of camera phone footage was central to that becoming public knowledge. Social media influences how we see ourselves, but it also changes how we see the world.

A: Hair and hairstyles are an important part of your work, especially in iconic portraits like Afro Hair and Beauty Show. Why did this idea become so central to your practice?

EP: At the time that I did the Afro Hair and Beauty Show series, I felt like I wasn’t seeing images like that in the mass media. If there was a person of colour, they were usually the pinnacle of success like a musician or an athlete, or it went the other way and there’d be negative portrayals, such as charity campaigns of children starving in Africa. That was the kind of extremes you had. I grew up in the 1980s and 1990s, and there were definitely the beginnings of positive Black role models, but it was still very limited. I documented real people who looked good. I wanted to hang these types of images on the walls of galleries, because you just didn’t see that in the museum space.

A: When you reflect on your career, are there any moments that you are particularly proud of?

EP: Obviously that trip to Ghana shifted so much for me, it was a defining moment in both my personal and creative identity and shaped how I view myself, my family and community. Other than that, I’m really glad I made Grace (2000), which featured people with gaps in their front teeth. This series includes the last photograph I took of my Mum. She came along to the Royal College, and I took her portrait. That happened in February, and she passed away unexpectedly in April. I then decided to name this series after her. I’m so pleased I have that. Photography has given me a gateway into a life that I could never have imagined. I’ve been able to travel to new places and capture different communities. I did a commission for King’s College Law School in 2015. I went into their library and it was like something from a Harry Potter book. I’d never have seen that if it wasn’t for my career. I’m honoured to say that I take photographs for a living.

A: Is there a person or portrait that has stuck with you?

EP: Different communities come to mind for different reasons. I had an exhibition with Pump House Gallery years ago, and it was part of an outreach programme. I ran a series of workshops with a group of adults from Wandsworth Mind, a mental health charity that ran a day centre. We did some photography together and went to see an exhibition at Photo Fusion. Daniel Meadows’ work was on show at the time, and some people really resonated with it. I was just interested in how individuals found their voices through each session, and the vulnerability and openness of those taking part. Of course, the images of my family are also very important to me. Some people have passed away since they were taken, so I’m really glad that photography gave me the urge to document the people around me.

A: What do you hope audiences take away from viewing your work?

EP: It’s funny, I never thought an exhibition like this would happen to me so to have this level of recognition is amazing. I hope the show makes people who are starting out feel like anything is possible. Especially for Black, female creatives, who often face more barriers to getting their work seen, I hope it gives them hope to follow their dream. Even if their calling isn’t photography, just to throw yourself into whatever you are passionate about and really engage with it.

A Thousand Small Stories is at Autograph, London until 13 September: autograph.org.uk

Words: Emma Jacob & Eileen Perrier

Image credits:

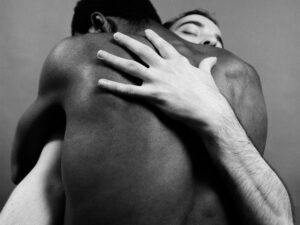

1&6. Eileen Perrier, from Afro Hair and Beauty Show, 1998-2003. Courtesy the artist and Autograph.

2. Eileen Perrier, from the series Ghana, 1995-1996. Courtesy the artist and Autograph, London.

3. Eileen Perrier, from the series Grace, 2000. Courtesy the artist and Autograph, London.

4. Eileen Perrier, from the series Ghana, 1995-1996. Courtesy the artist and Autograph, London.

5. Eileen Perrier, from the series Afro Hair and Beauty Show, 1998-2003. Courtesy the artist and Autograph.