Whitechapel Gallery is a bastion of artistic innovation. It’s a space where avant-garde ideas collide with cultural heritage to shape the evolving landscape of contemporary art. From Jackson Pollock’s first major UK show in 1958 to the landmark exhibitions of Frida Kahlo, Barbara Hepworth, and Gilbert & George, its walls have borne witness to some of the most defining moments in modern art history. Now, in 2025, the gallery continues this legacy with Donald Rodney: Visceral Canker, an exhibition that not only reintroduces a pioneering voice in British art but also reaffirms Whitechapel’s commitment to amplifying underrepresented narratives.

Donald Rodney (1961 – 1998) was an artist of extraordinary depth and insight. His work- spanning painting, installation, photography and digital media – was a radical act of both resistance and revelation. Born in West Bromwich to Jamaican parents, Rodney grew up in Smethwick, an area marked by the tensions of postcolonial migration and racial politics. As a founding member of the Blk Art Group in the 1980s, he was at the forefront of Black British art, creating works that interrogated race, illness, and the body as sites of personal and collective history.

“Rodney’s art was both deeply personal and politically urgent,” says Gilane Tawadros, co-curator of the Whitechapel iteration of the show. “His ability to collapse the personal with the political – drawing from his lived experience with sickle cell anaemia while addressing the systemic illnesses of society – remains as potent today as it was in his lifetime.”

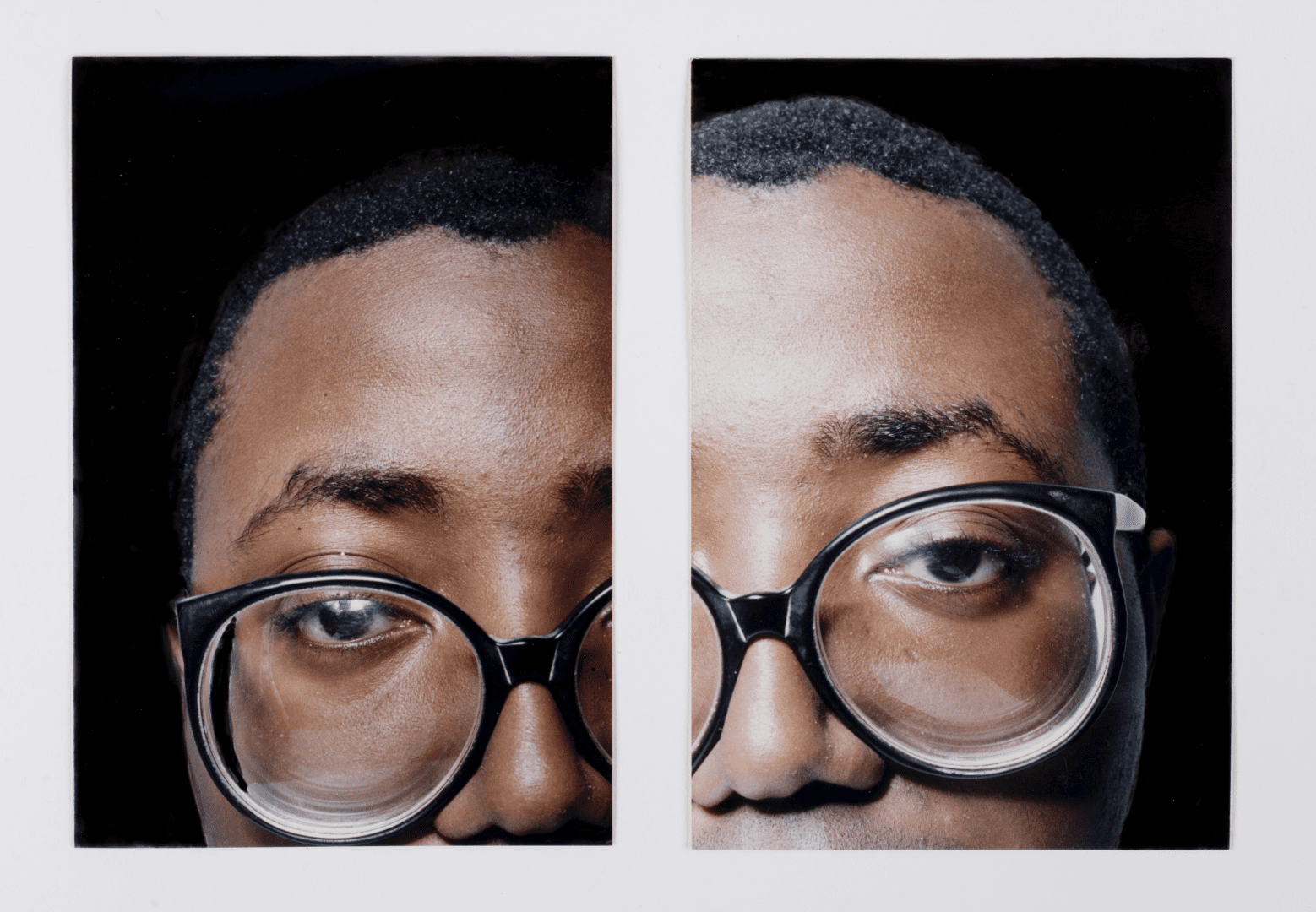

Following acclaimed runs at Spike Island, Bristol, and Nottingham Contemporary, Visceral Canker brings together the majority of Rodney’s surviving works, spanning 1982 to 1997. The exhibition’s title is drawn from a seminal 1990 piece in which heraldic plaques are linked by medical tubing, pumping theatrical blood in a stark commentary on colonialism’s enduring wounds. Amongst the standout works is The House That Jack Built (1987), a haunting mixed-media installation featuring a fragile house structure constructed from medical X-rays. The figure seated before it, a spectral presence, evokes both vulnerability and defiance. Elsewhere, Cataract (1991), a newly reconstructed 35mm slide installation, overlays fragmented images of Black male faces- Rodney’s included – exploring the ways in which Black identity is fractured and denied agency.

Rodney’s use of X-rays was more than aesthetic; it was profoundly autobiographical. Living with sickle cell anaemia, a hereditary disease disproportionately affecting people of African and Caribbean descent, he turned medical imagery into a visual metaphor for structural inequality. “His body became a canvas,” notes co-curator Robert Leckie. “Every X-ray, every fragment, was a political act- forcing visibility onto a body that the system often overlooked.”

Perhaps the most intriguing inclusion in the Whitechapel presentation is Camouflage (1997), a work Rodney exhibited at South London Gallery just before his death. A large camouflage fabric stretches across the space, subtly stitched with a racial slur – its near-invisibility a chilling reminder of racism’s insidious presence in everyday life. The power of this piece lies in its quiet subversion: the words are there, hidden yet present, much like the biases they expose.

Another highlight is Autoicon (1997 – 2000), a digital artwork Rodney conceptualised before his death and was completed posthumously by his collaborators, “Donald Rodney plc.” This pioneering work – a precursor to contemporary AI explorations – uses machine learning to simulate Rodney’s presence, drawing on a vast archive of his notes, interviews, and medical records. In an era where digital identities and AI ethics are fiercely debated, Autoicon feels eerily prescient.

Alongside the exhibition, Whitechapel Gallery is hosting a rich programme of talks, screenings, and archival displays. A particularly compelling panel discussion, What Lies Beneath the Surface: On Donald Rodney & The Politics of the Body, promises to unpack the intersection of race, illness and visibility in Rodney’s work. Meanwhile, Home as Sanctuary, Body in a State of Siege, a curated film series, extends his concerns into contemporary moving-image practices.

Rodney’s practice was relentless in its pursuit of truth, unflinching in its critique of power, yet deeply human in its execution. His untimely death at 36 left behind a body of work that continues to resonate, not just within the art world but across wider conversations about race, health and representation. “Donald Rodney was an artist ahead of his time,” reflects Tawadros. “His work anticipated the dialogues we are still having – about colonial legacies, about systemic racism, about how illness is experienced differently across different bodies. Visceral Canker is not just a retrospective; it’s a reassertion of Rodney’s place in the canon of British art.”

Curated by a team including Gasworks Director Robert Leckie, Spike Island Director Nicole Yip, and Whitechapel’s own Gilane Tawadros, Visceral Canker is more than an exhibition – it is a necessary re-engagement with one of the most vital artists of the late 20th century. As contemporary art continues to grapple with issues of identity and inequity, Rodney’s work stands as both a mirror and a map, guiding us through history toward a more just future.

The exhibition continues until 4 May. Visit whitechapelgallery.org for more information and to book tickets.

Words: Anna Müller

Image credits:

Donald Rodney. In the House of My Father, 1997. Photograph 123 Å~ 153 cm. Image © The Donald Rodney Estate.

Donald Rodney. Photograph used in preparation for Flesh of My Flesh, 1996. Sepia toned photographic print. Image © The Donald Rodney Estate.

Donald Rodney. Photographs with hand tinted black background used to produce the slide tape work Cataract 1991. Photos: Viv Reiss. Courtesy The Estate of Donald Rodney. Photo: Frederic Griffiths.

Donald Rodney. John Barnes (1991) and Mexico Olympics (1991). Duratrans prints on aluminium framed lightboxes with fluorescent tube lights. Each: 107 Å~ 81 Å~ 17 cm. The British Council Collection. Installation view: Spike Island, Bristol / Photo: Lisa Whiting.