Photographer Robert Giard (1939-2002) made connections between LGBTQ+ cultural producers of the late 20th-century. The Leslie-Lohman Museum of Art, New York, highlights his expansive practice, from nudes to still lifes and landscapes, as well as portraits of activists and artists. Curators Ariel Goldberg and Noam Parness discuss the show, titled Uncanny Effects: Robert Giard’s Currents of Connections.

Whilst the museum is closed, the exhibition is available to tour virtually on Instagram (@leslielohmanmuseum).

A: Particular Voices: Portraits of Gay and Lesbian Writers is the photographer’s most well-known project, documenting over 600 LGBTQ authors. What was the motivation behind the series?

NP/AG: Particular Voices: Portraits of Gay and Lesbian Writers was a project that Robert Giard began in the summer of 1985. After attending two plays – William Hoffman’s As Is and Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart – Giard was catalysed to create an archive of images of what he termed “gay” and “lesbian” authors, though the project also included authors identifying as bisexual and transgender. In a journal entry at the beginning of the project, Giard recalls that “several major threads in my life were being woven together: my homosexuality, art and literature, my being a portrait photographer, and a preoccupation with mortality.” In the height of the early years of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in New York, Giard felt it imperative to remember those who were dying.

A: Can you describe the process Giard took in creating such an expansive body of work?

NP/AG: Giard was a self-taught photographer. He set up a small darkroom for printing in his Amagansett home in 1973-4. This is the room in which he would create all his prints until his death in 2002. He alternated between 35mm and medium format film between the late 1970s and early 1980s, with medium format becoming the dominant form by the time he began Particular Voices in 1985. This series, specifically, was an incredibly laborious and careful process. Before each photoshoot with an author, Giard would be sure to read their writings to get a sense of their literary contributions. Correspondence would be mailed back-and-forth. Giard often left a portrait session with additional names, phone numbers and addresses for future portraits. His process is marked not only by the pace of analogue film, but an analogue network. Giard also never had a driver’s license, so he had to travel via public transportation, often by bus, around the country to work on this project.

A: Why is it important to showcase his work now, in 2020?

NP/AG: We now live inside an image culture where queer and trans people have faster and easier access to visually document and share their lives with camera phones and social media. The comparative slowness of Giard’s practice contrasts with modes of photographing today. Suggestions of who to follow were not presented by an algorithm, but through in-person conversations and correspondences that relied on the durational movements of the postal systems, landlines and answering machines. In exhibiting Giard’s analogue practice, we hope to reveal how much attentive contact and connectivity underscored Giard’s image-making. We have been able to study Giard’s rich practice through his journal entries, contact sheets, teaching notes and commercial gigs.

A: Which other genres did Giard work in – aside from portraiture? What messages do these wider works convey?

NP/AG: Giard worked within the genres of landscape, still-life and the nude, as well as portraiture. Early landscapes from his Grounds series are featured in the exhibition. These were usually taken in the Hamptons during “off season” in late autumn winter and early spring – capturing these spaces without human interaction. He viewed this series as “still another version of the pastoral, a more suburban version… but nonetheless vaguely menacing.”

Some of Giard’s earliest known work is a series of nude self-portraits where various parts of his body are hidden and revealed using a draped cloth. His male nude works (though he photographed women as well, as seen in the exhibition) gained traction in the late 1970s and early 1980s. These images were featured in exhibitionswith now-recognised photographers such as Alvin Baltrop, George Dureau, Peter Hujar and Robert Mapplethorpe. Giard, however, came to understand the nude as another form of portraiture. In an undated statement, he wrote that: “rather than being an example of the nude, they are pictures of people who are naked.” This can be glimpsed by an overlap into Particular Voices, such as the 1994 nude portrait of Scott O’Hara, an author, editor, activist and porn actor.

Still lifes were a constant practice of Giard’s, though they’ve received less attention. Different images appear humorous, erotic, contemplative, or mournful, depending on the individual work. Occasionally we found that Giard would create still lifes within the Particular Voices series as tributes to authors who died before he could reach them. In this sense, his still lifes occasionally cross over into the genre of portraiture.

A: How does the show foreground the relationships between the photographer and his sitters?

NP/AG: The exhibition includes a number of journal entries by Giard, which are at the heart of understanding his process. In addition to a digital display of 18 entries, we have excerpted Giard’s journal entries for our object labels. These feature his recollections, as well as responses from the sitters – both from around the time the images were taken and more recently. The exhibition not only looks at the relationships between Giard and his sitters, it also displays the links between those who sat for Giard’s images. The sitters’ cultural contributions are on display through writing, audio and film. We feature late 20th century LGBTQ journals and publications (such as Conditions, Black/Out, and Aché) that display the connections between those Giard photographed. These highlight the ways that publications allowed for the flourishing of literary networks, and circle back to how Giard was led from one sitter to another, eventually photographing over 600 authors.

A: So, the exhibition combines text and image. What else does the writing add to the experience of viewing the works?

NP/AG: When he began Particular Voices, Giard journaled for each photo shoot, using this practice to meditate on his sitters’ (and his own) mood and experiences, recording attractions, ambivalence and resistance to the camera’s and his own gaze. In later photography projects, both commissioned and personal, Giard would include his own writings alongside his images. The placement of these earlier journals in conversation with these photographs underscores the centrality of his writing practice. We see this exhibition as a portrait of Giard the writer, the photographer, and the voracious reader.

Find out more here.

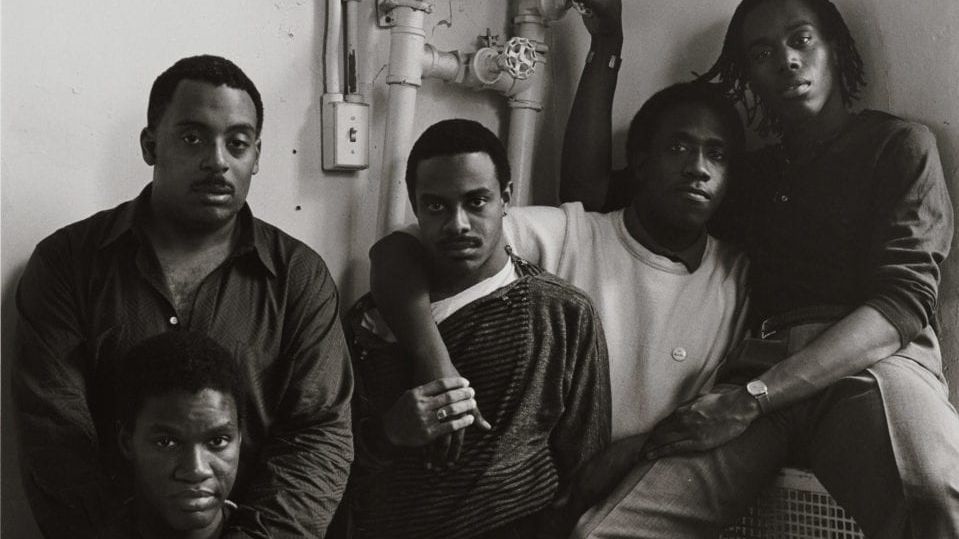

Lead image: Robert Giard, Five Members of Other Countries, 1987. Split-toned silver gelatin print, 14 x 14 in. Courtesy of Stephen Bulger Gallery, Toronto.

1. Robert Giard, Lines of a Golf Course, 1979. Split-toned silver gelatin print, 14 x 14 in. Courtesy of the Estate of Robert Giard.

2. Robert Giard, Cheryl Clark and Jewelle Gomez, 1987. Split-toned silver gelatin print, 14 x 14 in. Courtesy of the Estate of Robert Giard.