American artist Matthew Adam Ross, based in Los Angeles and New York, considers his practice to be a line of enquiry. It is an expression of the fundamental questions we usually only ask ourselves in private moments. He notes: “The questions I ask are the life rafts to rescue the nostalgia in me, that I dare hope and dare believe is in you and is in us.” We speak with him to find out more.

A: How far do you feel that your works have a sense of narrative?

MAR: Much of my older works on canvas took on less of a narrative and were more studies of the beauty of tension and an exploration of the codependency between chaos and negative space.

My newest works deal with narratives surrounding the concept of contemporary ruin in American society as well as man’s historical relationship with the built environment. Some of my newer works with zip ties closely examine synaptogenesis and its relationship to the way trends rise and fall so rapidly in contemporary society.

A: Where do the pieces draw a line between tradition and contemporariness?

MAR: The artistic movement I identify most closely with is post-minimalism, and I feel that a line is drawn with my works when looking at the way I manipulate certain materials to do things that they are typically not supposed to do, as well as some of the cross-disciplinary references I am incorporating. While I am gratefully influenced, I do feel that much of my newer works are breaking new ground with the way certain materials can be manipulated, layered and conceptually relevant.

A: There is a sense of movement within each composition – across the frame and within the shapes themselves. Could you describe the process behind this and how it communicates a human element within the images?

MAR: I have always taken influence from many cross-disciplinary genres and incorporate them into my pieces, areas such as mathematics, psychology, science, philosophy, history, archaeology and heavy industry. Much of my mark marking has evolved in a melting pot of these disciplines, in a way where they coexist rather than challenge each other.

As far as movement across the pieces, I never want to get stuck in a piece – I want to flow through it and feel a sense of wonder, like I’m discovering or uncovering something.

Human intervention is a large part of my current work, in particular the concept of the urban vernacular, which can be defined as ambiguous, dire and vulnerable mark making, similar to something you’d see scribed in a public setting, like a bus stop, a window of a bodega, the top of a desk. Unlike most graffiti, they are journal entries not intended for a third party.

A: You see your work as a line of enquiry – how do the abstract shapes and forms provoke questions in the viewer and why do you think this is important?

MAR: With my current series, I intend for my audience to explore the idea of contemporary ruin, and how the objects I am creating could be interpreted as roadmaps to the infrastructural identity of our society.

I am fascinated with the idea of morphology, particularly in Western society, and how it relates to the neglect and rapid changes we see in the built environment as well as in contemporary American thought. Trends come and go in hysterical fashion, partially because, as Americans, we do lack a sense of historical continuity and identity because of how young our country is.

This has a strong effect on the way we perceive our environment and how we interact. We previously discussed my incorporation of historical and archaeological theory in my current works, in particular, stylistic references to Roman ruins that occurred during its fall. The colours and shapes of my works can be traced to the colours of curbs and what rules they represent; they are presented as artifacts and ruins.

A: How has your earlier work as a union welder in New York informed and inspired your art practice?

MAR: Welding and doing fabrication work in New York acted essentially as a training ground for what I am currently exploring with industrial materials. Much of the works I am producing now do require a knowledge of material and building theory, as well as an understanding of structural properties, especially with concrete and the malleability of metals. I also feel that I have been given a library of materials to draw inspiration from and manipulate, based on years of experience with them.

A: To what extent do you think one’s previous upbringing, education and employment affects one’s creation of art?

MAR: I find that all of those points are interrelated and in some way, shape or form are traceable in the artistic style of most artists, whether intentional or subconscious. However, each point will likely have varying degrees of impact depending on the individual. For me, I can trace distinct influence from all of these areas.

A: You did a residency at the Berlin Art Institute in 2016. How did this further your art practice? What is more important for you: the location of a residency or its atmosphere?

MAR: My residency at BAI pushed me to explore a vast network of materials and to explore the use of found objects. I think both are very important and impactful, but for me, the residency itself is most important. I would do a residency in what many would perceive as an undesirable location if it meant I would absorb invaluable experiences that would push my work into presently unknown or even inconceivable areas.

A: How often do you travel between New York and Los Angeles? How do you find the similarities and differences between the art scenes in these two cities?

MAR: I am typically back and forth every 2–3 months. My main studio is in the Echo Park neighborhood of LA, and the more time I spend here, the more I feel a strong sense of community and common ground in the art world here. It feels more uncalculated, unknown and undefinable to me.

The commercial element isn’t as predominant, even though there are plenty of collectors and wealth to sustain a career, and I find many artists making works that aren’t necessarily even intended for sale, which I respect and admire. It’s a tormenting necessity for a lot of artists here to make work, not as much of an intentional path.

www.matthewadamross.com

www.instagram.com/matthewadamross

The work of Matthew Adam Ross appears in the Artists’ Directory in Issue 83 of Aesthetica. To pick up a copy, visit our shop: www.aestheticamagazine.com/shop

Credits:

1. Contemporary Ruin I. Concrete, brass, aluminium, steel, markings with chisel, drill, hammer and grinder, 44in x 50in.

2. Contemporary Ruin II. Concrete, brass, copper, steel, markings with chisel, drill, hammer and grinder, 44in x 50in.

3. Contemporary Ruin III. Broken concrete on brass, 30in x 24in.

4. Synaptogenesis. Zip ties on painted steel grid, 60in x 26in.

5. Preserved Yellow Curb I & II. Figure I (right): concrete on steel grid, oil, utility paint, graphite, held with zip ties on cleat, 40in x 33in. Figure II (left): cinder blocks, concrete, steel grid, oil, utility paint, 6ft.

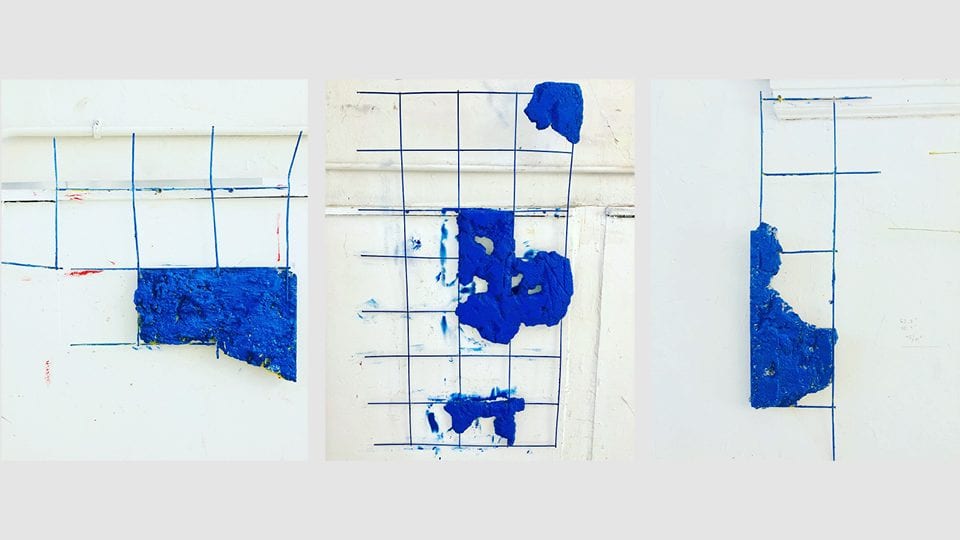

6-8. Preserved Blue Curbs. Concrete on steel grid, oil and utility paint.

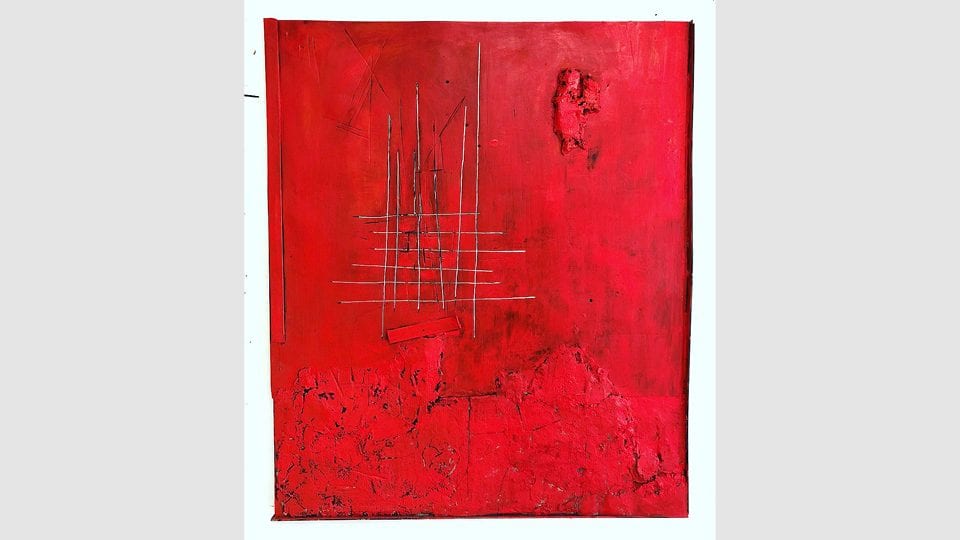

9. Preserved Red Curb III. Concrete, steel, oil, utility paint on steel panel, markings with grinder, 50in x 44in.

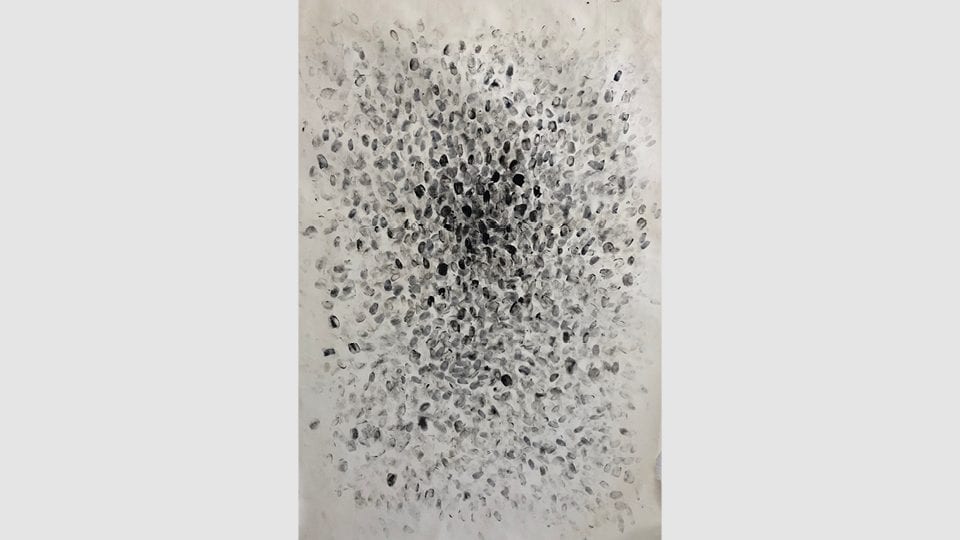

10. Study of Weathered Identity. Fingerprints with booking ink on paper, 36in x 50in.