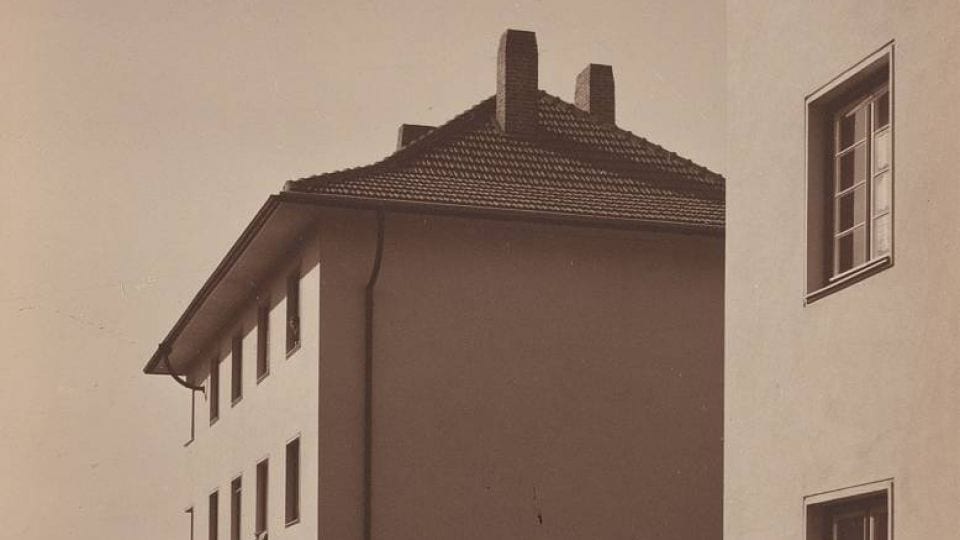

Born and raised in Cologne and known primarily for his iconic photographs of the Neues Bauen movement of modernist architecture that emerged there in the 1920s, Werner Mantz (1901-1983) established a successful practice in his home town. After opening a studio there in 1921, he captured many an artist, politician and famous intellectual before receiving commissions from architects, such as Wilhelm Riphahn, Peter Franz Nöcker, Caspar Maria Grod and other avant-garde representatives of the medium.

Published in architectural journals, the images that Mantz produced possess a technical finesse that endows the buildings with an almost majestic presence, despite their cold hard lines and functionality. After working for over ten years as a photographer in Cologne and capturing world famous buildings, such as the Kölnische Zeitung newspaper offices and the Blauer Hof housing estate (1926), Mantz opened a second studio in Maastricht in 1932. It was here that he became well-known for portrait photography, mostly specializing in pictures of children.

In a new exhibition titled Architecture and People, the Nederlands Fotomuseum in Rotterdam brings Mantz’s architectural and portrait works together to shine new light on his working methods. As a joint exhibition with Museum Ludwig in Cologne, the display shows collections from both institutions together and curates the images by form rather than by geography or chronology. This unique approach provides compelling insights into Mantz’s interest in the behaviour of light and how it can be used to give shape and character to both architectural and human form. Despite seeing himself primarily as a craftsman, viewing the images side by side highlights Mantz’s quality as an artist. In the arresting image Communion Portrait of a Girl, Limburg from 1959, for example, the attention to light and atmosphere echoes that of earlier architectural photos from his oeuvre.

Museum Ludwig’s curator, Miriam Halwani has commented on the striking effect of Mantz’s images, explaining that, “as banal as his subjects seem at first glance, I was surprised by the coolness and eeriness that his pictures exude. The buildings that he photographed are devoid of people, clean, almost virtual. We do not know the identities of the people in the portraits taken in his studio in the 1950s. In a way, we are only left with outer shells. And it is precisely for this reason that the these pictures persist in our memory.”

Until 2 September. Find out more at Nederlands Fotomuseum.

Celia Graham-Dixon

Credits:

1. VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017, Werner Mantz / Nederlands, Fotomuseum, Foto: Nederlands Fotomuseum, Rotterdam.

Join the Conversation. Follow us on Instagram, Twitter, Facebook and Pinterest.