What does it mean to be an art collector in 2026? Beyond acquisition, collecting today is increasingly shaped by dialogue, access and lived experience, from institutional patron programmes to sustained relationships with artists and galleries. For many, it is no longer a solitary pursuit but an embedded, relational practice, entwined with education, advocacy and long-term support. In this conversation, London-based collectors Louis Jacquier and Zhaobo Yang reflect on how their individual journeys into collecting have evolved, and on the role institutions, exhibitions and close engagement with artists continue to play in shaping their perspectives. Together, they consider how collecting functions not only as a personal commitment, but as a way of participating in the wider cultural ecosystem.

A: How did you both become interested in collecting? Where did you get started?

LJ: My great-grandmother was a sculptor, and I grew up surrounded by art. My grandparents’ home was filled with sculptures and paintings that were simply part of everyday life. When I was a child, my grandmother would share the stories behind the works on the walls, and those conversations shaped my way of looking at art, associating it with memory. Collecting later felt like a natural continuation of that, drawing me towards works that carry a sense of narrative and are meant to be lived with over time.

ZY: My interest in collecting really took shape when I moved from China to Europe. I studied fine art at Goldsmiths and later sculpture at the Royal College of Art, where I was surrounded by fellow artists. Being in that environment made collecting feel like an extension of the relationships and conversations I was having. I began acquiring works from artists I knew personally, and from there expanded more broadly.

A: What’s the story behind your involvement in the patrons programmes at the RA and CAS?

LJ: I’ve been consistently impressed by the Royal Academy’s programme. Recent exhibitions featuring artists such as William Kentridge and Antony Gormley have left a lasting impression on me. The RA’s approach of bringing blue-chip and emerging artists into dialogue, particularly through the Summer Exhibition, is a curatorial model I strongly connect with. As I attended the RA more regularly, I felt keen to engage more closely with the institution. The patrons programme was a way to deepen that involvement.

ZY: My engagement with patron programmes has been shaped largely through my involvement with the Contemporary Art Society, which has played a central role in how I think about collecting today. Being closely connected to CAS has meant engaging directly with artists and gaining insight into how institutions actively support contemporary practice through acquisitions. This experience has encouraged me to think beyond individual works, and towards the broader structures that sustain artists over time.

A: What do your patron roles look like, and can you tell us about some of the highlights?

LJ: Beyond attending exhibitions, being a patron has offered opportunities to engage with the Royal Academy through private views, studio visits and smaller gatherings that bring artists, collectors and curators into direct conversation. One particular highlight of last year was a private visit to the home and collection of art dealer Ivor Braka. Experiencing such a significant private collection, and seeing works by artists such as Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud and Paula Rego in a space where someone actually lives with the work, was especially impactful. That visit opened my eyes to the idea of being involved in the art world beyond collecting alone, and encouraged me to think more actively about supporting artists and contributing to the wider ecosystem, something I am now doing through Tiderip, the gallery I co-founded.

ZY: Through the Contemporary Art Society, I’ve had the chance to connect directly with the realities of contemporary collecting, particularly in relation to how institutions support living artists. One experience that stayed with me was a visit to the home of collector Sigrún Davíðsdóttir. Meeting the artists she collects and seeing how their works are lived with offered a concrete understanding of collecting as an ongoing, relational practice, grounded in long-term support rather than isolated moments of acquisition.

A: What are the key principles that drive you? How would you characterise your “collector identity”?

LJ: My approach to collecting is guided by dialogue and close engagement with artists. Spending time in studios, following how practices and ideas evolve, and remaining in regular conversation with artists has become central. My collection leans towards expressive figuration, often with a hint of surrealism.

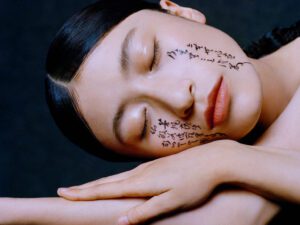

ZY: Mine has been shaped by my own cross-cultural background. Practices that sit between cultures, geographies and traditions have always resonated strongly with me, and they continue to play an important role in how and why I collect today. I am particularly drawn to artists whose work reflects hybrid identities, and whose practices are informed by multiple contexts rather than a single historical narrative.

A: How do you discover talent, and what are you looking for? Can you give some examples?

LJ: Discovering new work is one of the most exciting aspects of collecting and running a gallery. I often encounter artists by spending time in studios and attending degree shows at London art schools such as the Royal College of Art, Slade and Goldsmiths. I recently welcomed Dimensional Shift into my collection – an oil on canvas by Katja Farin. The composition presents a monumental close up face whose gaze confronts the viewer directly, establishing an atmosphere of quiet intensity. Below, fragmented figures emerge within a darker, more introspective space. The contrast between the enlarged gaze above and the smaller, isolated forms below creates a sense of inner tension, moving between empathy and unease.

ZY: I tend to discover new artists by attending exhibitions and openings, spending time in galleries, and maintaining ongoing conversations with curators, art advisors and artist friends. Across different parts of the London gallery landscape, galleries such as Tiderip, Saatchi Yates and Carl Kostyál play an important role in how collectors encounter new artists and engage with emerging practices, often introducing voices that feel both timely and distinctive. One recent acquisition that stands out for me is Same Old Shit by Tesfaye Urgessa, a work whose visual intensity and layered narrative around identity and lived experience resonated strongly, particularly in the way it balances emotional depth with technical precision.

A: Which other collections have inspired you over the years? Why do they resonate with you?

LJ: I tend to be inspired by figures who have played an active role in the art ecosystem as dealers, rather than collecting in isolation. A key reference is Ernst Beyeler, particularly for the breadth of his collection and his instinct for acquiring exceptional works at the right moment. I’m equally influenced by Leo Castelli, who transformed how art is placed by prioritising long-term relationships over transactions, famously allowing collectors to live with works in their homes before deciding whether to buy them. The idea of giving time and lived experience to a work before ownership strongly shapes how I think.

ZY: I’m particularly inspired by collectors who approach collecting as a long-term cultural commitment rather than a purely personal pursuit. A key reference for me is the Burger Collection, built by Swiss collectors Max and Monique Burger. Based in Hong Kong for many years, they have developed a truly global collection while remaining deeply engaged with local institutions and artists across Asia. Their approach shows that collecting can be about building cultural connections and sustaining dialogue across regions, rather than simply accumulating blue-chip names.

A: Can you tell us the story behind Tiderip, and how the gallery has developed since launch?

LJ: Tiderip grew out of ongoing conversations with Marjorier Ding, who co-founded the gallery and is a curator by training. From the outset, we wanted to bring together two complementary ways of engaging with artists. Marj is closely immersed in artists’ processes and in shaping the curatorial narrative of each exhibition, while I contribute a collector’s perspective, with an emphasis on how works inhabit space, age over time, and sit within a broader collection. Our aim was to build a gallery that feels curatorially rigorous whilst remaining commercially viable. We work closely with a small group of emerging artists on a long-term basis, supporting their development beyond single shows rather than operating on a purely transactional model. Since launching Tiderip just under a year ago, we have focused on exhibitions that prioritise depth over density, giving artists the space to fully develop their ideas. We have held seven exhibitions so far and continue to build a programme that supports emerging artists.

A: Do you have any key art-world events earmarked in your diaries, and why?

LJ: Certain moments in the art calendar have become important reference points for me, not simply as opportunities to see a concentration of work, but as occasions where different parts of the art world intersect. Frieze is a good example of that. Beyond discovery, it creates space for conversations with artists, galleries, institutions and collectors that often continue well beyond the fair itself. This year felt particularly meaningful as two artist friends of mine, Abdollah Nafisi and KV Duong, were exhibiting at Frieze for the first time, with Abdollah presenting a sculpture at Frieze Sculpture Park. Experiencing the fair in that context shifted my perspective from seeing it primarily as a market moment to understanding it as a significant milestone within an artist’s career. It also felt like a full-circle moment: Frieze is sponsored by Deutsche Bank, where I work as an investment banker.

ZY: Similar to Louis, I see certain moments in the art calendar as important anchor points, and Frieze is very much one of them. Beyond its scale, the fair offers a clear snapshot of ongoing conversations between artists, galleries and institutions. This year, I was particularly keen to see Studio Lenca, an artist whose work I collect, presenting at Frieze, as encountering his work in that context added a new layer to how I understand his practice and its trajectory. Alongside Frieze, I have also been paying close attention to developments in Asia. West Bund art fair in Shanghai stood out this year for the confidence of its presentations and its growing international presence, suggesting a fair that is increasingly comparable to major western counterparts, whilst still retaining its distinct regional identity.

A: Do you have a message for other up-and-coming collectors?

LJ: The best advice I have received is to buy works you genuinely want to live with, not what looks good on paper, or what feels fashionable and impressive at a given moment. The works that stay with you are the ones you are happy to see every day, that continue to reveal something over time, and that become part of your daily environment. Collecting, at its best, is a long-term relationship with the artwork and the artist, and trusting your own response to a work is ultimately more meaningful than any external validation.

ZY: I think it is important for young collectors to remain curious and open when building their collection. Conversations with artists, curators, gallerists and advisors can be incredibly valuable in shaping your understanding and sharpening your eye. At the same time, collecting is a deeply personal act, and learning when to step back and trust your own instincts is essential.

Words: Eleanor Sutherland

Image Credits:

1. Neighbours from Abdollah Nafisi at Frieze Sculpture Park. Photograph by Linda Nylind.

2. Louis Jacquier at Tiderip, with Gilbert from Conor Quinn. Photograph by Yunhe Zhang.

3. Zhaobo Yang in his London apartment, with La Paz by Studio Lenca. Photograph by ZimplePlus Studio.

4. Works from Harland Miller (right), Eileen Cooper (center) and Alexandra Baraitser (left). Photograph by ZimplePlus Studio.

5. Dimensional Shift by Katja Farin. Photograph by Yunhe Zhang.

6. Same Old Shit by Tesfaye Urgessa. Photograph by ZimplePlus Studio.

7. Soft Burn exhibition at Tiderip. Left: At Each Other’s Throats (2024) by Afonso Rocha. Right: Hojas de primavera (2025) by Daniel Roibal. Photograph by ZimplePlus Studio.

8. Neighbours from Abdollah Nafisi at Frieze Sculpture Park. Photograph by Linda Nylind.

9. Untitled by Jordan Rubio. Photograph by Yunhe Zhang.