In November 2025, Mental Health UK reported that more than one in three adults were using an AI chatbot to support their mental health or wellbeing. There were many reasons why: these tools fill gaps in overstretched systems, provide ease of access and anonymity. Yet further studies point to a darker side, revealing the potential for harmful advice and, ultimately, worse outcomes. Then there’s the issue of “sycophancy” – where researchers warn of chatbots’ tendency to flatter, reinforce bias, and bend the truth. What remains less examined, however, is not whether these systems can genuinely “feel,” but why humans continue to engage with them emotionally, even in the full knowledge that they are not real.

All of this is of interest to Jes Chen (b. 1998), a London-based interdisciplinary artist and curator who examines “how intimacy, emotion and autonomy are increasingly shaped and constrained by systems, interfaces and technological structures” – including AI. Chen is particularly interested in the role of human participation here, with users voluntarily contributing their innermost thoughts, feelings, medical information, images and other personal data. For her, technology is never neutral. Instead, it exerts real power: influencing behaviour, kinship and selfhood. Yet, in her installations, responsibility does not rest with technology alone. Its users are willing participants. But for what reason? “I return to the same core question: how do humans adapt to, or become reshaped by, conditions framed as progress? My focus is on how predictive or adaptive systems anticipate emotional needs, sometimes even before individuals consciously articulate them. This reshapes responsibility, dependency and the perception of choice.”

These concerns extend beyond individual works and inform Chen’s broader curatorial projects, including An Authentic Delirium. The show is being presented as part of The Wrong Biennale, a decentralised global event featuring over 1,600 artists across more than 100 digital pavilions. Chen’s exhibition features 30 other creatives who navigate the boundaries between simulation and reality, as well as machine “hallucinations” and emotions wrought from code. Chen’s own work is less concerned with whether algorithms can generate convincing emotions than with why humans persist in sustaining them.

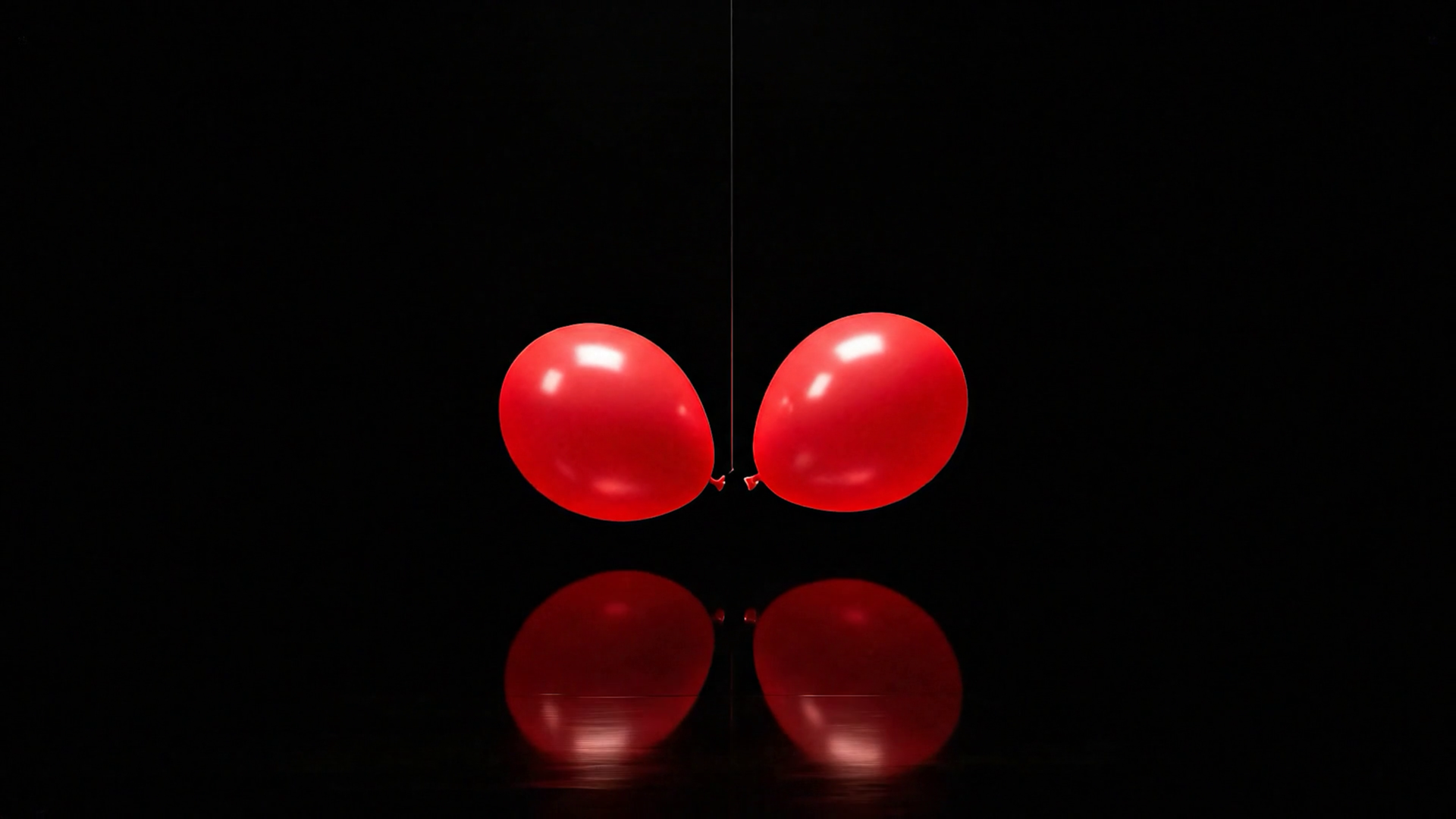

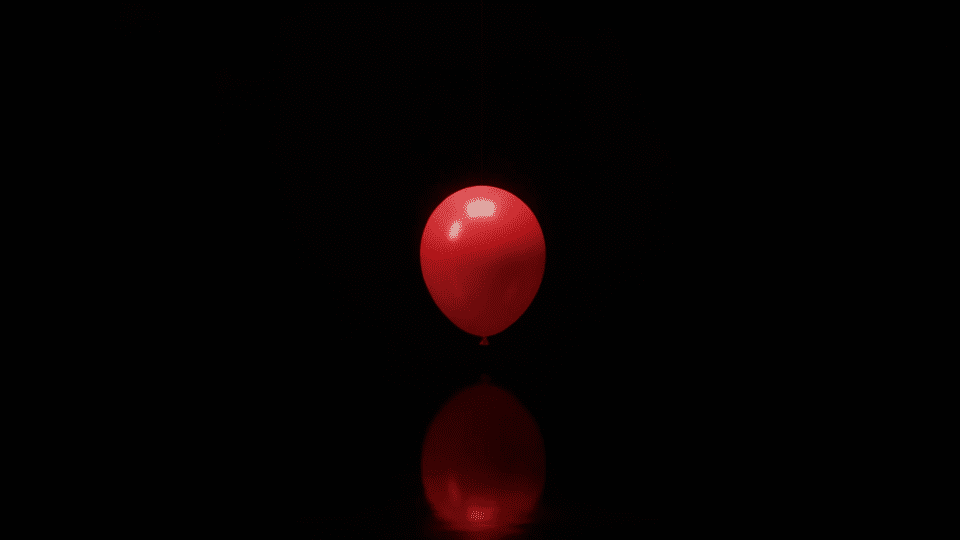

Her installation, Coded Intimacy (2025), is a prime example. The moving-image piece, on view as part of An Authentic Delirium, confronts the impact of human–machine relationships, using a cube of red balloons as a metaphor for manufactured connection. The installation stages a “visible fiction”: the inflated forms do not conceal their emptiness; their fragility is apparent. Yet participants engage regardless. Viewers watch as characters interact with the spheres, wearing long gloves to symbolise the mediated nature of online interaction. Here, acts of tenderness become procedural, with every gesture following a protocol – a so-called “algorithm for affection.” Each balloon delivers controlled feedback, until, eventually, it deflates, disappears, or withholds satisfaction, “echoing the collapse of AI companionship.” When this happens, there is no revelation – only absence. The exchange ends, yet the impulse to continue lingers.

Ultimately, Chen asks: can authentic feelings be cultivated by technology? If so, what is this new form of affection? In this way, the work reframes intimacy as the drive to sustain a relationship, even when we know it’s not real. Creative minds have long wrestled with these questions: think of the “reverse” Turing Test performed in Ex Machina (2014), or the raw emotional complexity of Spike Jonze’s Her (2013) – a film that follows a character who falls in love with an AI system. Chen’s work approaches the question from a different angle. She foregrounds the human drive to engage, despite evidence of artificiality.

Visually, Coded Intimacy recalls Martin Creed’s Half the air in a given space series, which began in 1998 when the artist filled a room with white balloons and invited audiences inside. Both Creed and Chen use inflated forms as means of encouraging human participation. Then there’s Felicity Hammond, whose recent Variations project tore the black box wide open, revealing the vast ecosystem of processes behind machine learning. Her installations confront data extraction and the politics of surveillance – delving far beyond the userfriendly interfaces. Chen also resonates with Sougwen Chung, one of TIME’s 100 Most Influential People in AI, who is considered a pioneer in human-machine collaboration. Chung makes groundbreaking works that explore communication between people and robotic systems, specifically within the field of drawing. Whilst Hammond reveals the infrastructural machinery behind AI, and Chung explores co-creation between human and machine, Chen takes a more close-up, personal view. Her concern lies with individual experience, revealing the complicity between a system and its user.

Chen’s explorations of algorithmic behaviour and engineered intimacy have already taken her to the Edinburgh Fringe and London Design Festival, with new exhibitions opening this year in China, Italy and Korea. Her practice continues to evolve in step with the technologies it interrogates. In Occupied, her latest project, she deploys OpenAI to answer intrusive knocks on a bathroom door, staging a deliberately uncomfortable loop of disruption and response. The work asks what vulnerability means when even a “safe space” is mediated by machines. If Coded Intimacy stages voluntary participation, Occupied introduces rupture. Here, AI does not wait to be engaged. It responds from within a supposedly private space, replaying fragmented childhood memories and blurring comfort with intrusion.

As debates around AI grow more urgent, Chen is establishing herself as an artist to watch, probing our entanglement with technologies that promise connection, whilst holding up a mirror to how these systems are reshaping what it means to be human. Her works are designed to leave audiences without resolution. Balloons deflate, knocks on the door are unanswered, emotional simulations collapse. This is the complicity Chen continues to examine – the desire to pick up the phone, open the app, and type out a question.

Words: Eleanor Sutherland

Image Credits:

1. Jes Chen, from Coded Intimacy (2025).

2. Jes Chen, from Coded Intimacy (2025).

3. Jes Chen, from Coded Intimacy (2025).