The very first Biennale was founded in 1895 in Venice, as an international exhibition designed to bring artists from across Europe together in the Giardini gardens, fostering exchange and dialogue between nations. Originally established as a celebration of artistic innovation, it created a precedent for large-scale exhibitions that could combine national pride with cross-cultural engagement. Over time, the Biennale expanded its remit beyond painting and sculpture to include architecture, film, performance and multimedia works. It is a festival of ideas, a convergence of memory, place and political reflection, where art ceases to exist in isolation and becomes a catalyst for social engagement. Biennales have continually adapted to address the pressing concerns of their times – colonial histories, urban development, climate crises, migration and identity – whilst fostering local cultural ecosystems and global networks. The biennale is not merely an exhibition; it is an instrument of cultural diplomacy and civic imagination.

Amongst the largest and most influential of these gatherings are the Venice Biennale, Documenta in Kassel, Germany, and the São Paulo Bienal in Brazil. Venice, now synonymous with the term itself, is a city transformed every two years into a labyrinth of curated pavilions, historic palazzos and ephemeral interventions, drawing audiences from across the globe. Documenta, staged every five years, is renowned for its rigorous conceptual approach, foregrounding political, social and philosophical concerns, often sparking debate far beyond its Hessian setting. The São Paulo Bienal, meanwhile, serves as a cultural beacon in Latin America, redefining the intersection between urban space, community engagement and artistic practice. Each of these events activate cities, drawing tourism, catalysing infrastructural renewal, and creating spaces where local and global narratives intersect. Through careful placemaking, they transform the city itself into an exhibition, embedding creativity into streets, museums and public arenas.

Sydney’s own biennale has followed a parallel trajectory since it started in 1973. As Australia’s largest art event of its kind, it has continually positioned the city as a locus of cultural experimentation, drawing international artists while foregrounding local voices. The 25th Biennale of Sydney, titled Rememory, continues this tradition, situating memory at the intersection of art, history and civic reflection. Curated by Hoor Al Qasimi, the edition invokes Toni Morrison’s notion of “rememory” to explore histories that have been erased or repressed, revealing the profound interconnections between place, identity and the stories we choose to preserve. Across five major exhibition sites – including White Bay Power Station, the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Chau Chak Wing Museum, Campbelltown Arts Centre and Penrith Regional Gallery – the biennale extends its reach into Western Sydney, embracing inclusivity and accessibility.

The placemaking dimension of the biennale is particularly compelling in Sydney, where artworks respond directly to the city’s geography and cultural landscape. White Bay Power Station, an industrial relic, is repurposed as a vast immersive environment, offering artists a canvas of unparalleled scale. Here, Nikesha Breeze’s Living Histories invites visitors to inhabit the narratives of enslaved African Americans, weaving large-scale fabric columns resembling Baobab trees into an archival reclamation of lost voices. Elsewhere, Penrith Regional Gallery will host Wendy Hubert’s native plant garden, a living installation that celebrates ancestral knowledge while offering communities space to gather, learn and share. Such interventions transform familiar urban and regional sites into arenas for contemplation and dialogue.

This year’s thematic remit is expansive yet precise, reflecting on erasure, reclamation and the enduring impact of colonial histories. Across Sydney, artists engage with marginalised narratives, intergenerational trauma, migration and the continuity of cultural knowledge. Nancy Yukuwal McDinny’s monumental mural at White Bay documents the experiences of the Gulf of Carpentaria’s traditional custodians, tracing conflicts from colonisation to contemporary mining practices. In parallel, Nahom Teklehaimanot’s canvases at the Art Gallery of New South Wales explore the refugee experience, presenting displacement as a delicate negotiation between exile and solidarity. Each work acts as both witness and interlocutor, offering viewers entry into histories that are seldom acknowledged in mainstream discourse.

A significant facet of the 2026 Biennale is its collaboration with the Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, which has commissioned 15 First Nations artists from around the world to create new work. This initiative amplifies voices historically marginalised, situating Indigenous and diasporic perspectives at the core of the exhibition. Frank Young’s Kulata Tjuta Project, for example, brings together three generations of Anangu spear-makers to create a monumental installation of hand-carved spears, maintaining and celebrating cultural traditions. Similarly, Behrouz Boochani, Hoda Afshar and Vernon Ah Kee’s Code Black/Riot confronts colonial legacies through the lens of Indigenous youth in detention, merging film, performance and social critique. Through these projects, the biennale not only presents artworks but actively cultivates intergenerational and cross-cultural exchange.

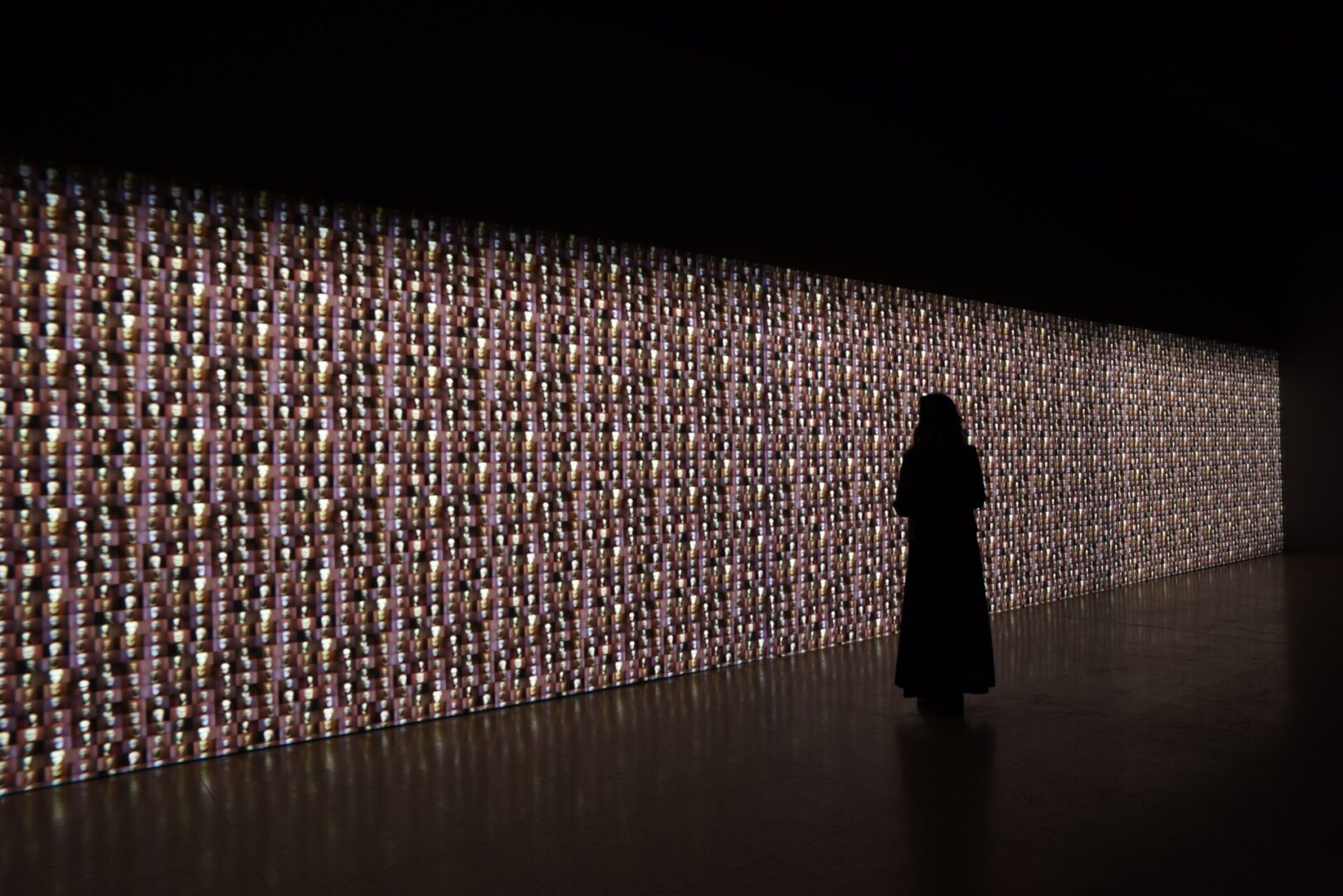

Migration, dreams and imagined utopias also resonate across the 2026 programming. Lebanese artists Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil Joreige present an immersive multimedia installation at Campbelltown Arts Centre, tracing the journey of friends migrating to Australia alongside the annual red crab migration. The project interweaves personal aspiration with ecological rhythms, creating a poetic meditation on movement and hope. Benjamin Work, a Tongan artist based in Auckland, interrogates archival colonial records and Tongan dress, highlighting how traditions adapted under foreign pressures as a strategy of autonomy. These works underscore the biennale’s ability to draw connections between local specificity and global histories, offering audiences multiple registers of interpretation and engagement.

Sound, performance and community programming form another crucial strand of Rememory. Joe Namy’s Automobile transforms cars into participatory instruments, blending music, mechanics and social gathering. Dennis Golding revisits Redfern, leading workshops and tours that reflect on Aboriginal histories and lived experiences of the neighbourhood, while Art After Dark at White Bay Power Station enlivens the space with performances. These interventions exemplify the biennale’s investment in participatory engagement. Education programs for students, family days and community workshops further reinforce this ethos, ensuring that artistic exploration is accessible across generations.

By foregrounding marginalised voices and fostering dialogue between international and local artists, the exhibition reaffirms art’s power to confront, inspire and transform. It situates Sydney not only as a host city but as an active participant in the processes of cultural reflection and regeneration. With site-specific projects across the city, monumental installations, public programming and community engagement, the 25th Biennale promises to be an immersive and resonant experience, inviting audiences to inhabit histories, reimagine futures and participate in the ongoing act of cultural rememory.

As Sydney prepares to welcome visitors from 14 March – 14 June 2026, this edition offers a vivid reminder of the biennale’s capacity to bridge time, place and perspective. The city itself becomes both stage and participant, where the legacy of past injustices is acknowledged and celebrated, and art asserts its essential role in shaping public consciousness. In revisiting, reconstructing and reclaiming memory, the Biennale of Sydney demonstrates that exhibitions are instruments for sustaining cultural dialogue for generations to come. The 25th edition stands as a testament to the transformative potential of biennales worldwide – a celebration of creativity, history and the human stories that bind us together.

The Biennale of Sydney runs from 14 March – 14 June: biennaleofsydney.art

Words: Anna Müller

Image Credits:

1. Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil Joreige,Where Is My Mind?, 2020 © Joana Hadjithomas, Khalil Joreige and Sursock Museum.

2. Basil Al-Rawi, Feint Recollections of a Time Beyond, 2024, video still, single-channel video, 20 min. Photograph: Basil Al-Rawi. Courtesy of the artist. ©Basil Al-Rawi.

3.Here We Stand, 2022. Installation Dimensions variable Courtesy of the artist Photograph: Carmen Glynn-Braun.

4. DAAR, Concrete Tent, 2023, wood, concrete and yuta, 5 x7 meters. Commissioned by Sharjah Architecture Triennal. Photograph: Edmund Sumner. Courtesy of the artists© Alessandro Petit.

5. John Harvey & Walter Waia, Katele (Mudskipper)(video still), 2023, film, 14 minutes.Courtesy of the artists, Brown Cabs & Kalori Productions. (detail)