Ben Cullen Williams (b. 1988) is a London-based artist working across sculpture, installation, photography and video. His practice explores the relationship between space, technology and landscape, drawing on both physical and digital processes to interrogate how material systems are shaped, mediated and transformed. In 2021, Williams was longlisted for the Aesthetica Art Prize for Living Archive: An AI Performance Experiment, a collaboration with Google Arts & Culture and choreographer Wayne McGregor. His latest project, Self Portrait, was developed in collaboration with Google Arts and Culture and Google DeepMind Research Scientist Jason Baldridge. For the work, Williams prompted a generative AI to describe itself before training the model on his own images, producing a self-portrait that merges the machine’s self-image with the artist’s vision. The project revisits the centuries-old question of what a self-portrait can be, reframing it for an era of generative systems. We caught up with the artist to discuss the process, what it means to make art alongside generative AI and how technology might shape his practice in the future.

A: Could you tell us about your journey into the arts?

BCW: I studied architecture before doing an MA in Sculpture at the Royal College of Art. Many of my interests stem from my initial studies in architecture and my larger sculptural works borrow visual language from that discipline. But I have always taken photographs: from a young age I had these great little point and shoot cameras, which I still use now. Constellations of photographs that I have taken are the bedrock of my practice. I form connections between them, and that helps me consolidate my ideas.

A: How do you use technology in your work?

BCW: Much of my work explores the human-made alterations of our natural landscapes and corporeal world. I do this through either looking at these technological alterations in my subject or using technology as the medium to change these landscapes further. I could use a combination of both, in the subject and also as medium. I like to see how different types of technology can present the world to us, for example, I might use 8mm film or CGI. The two modes of presentation bring with them another layer of meaning.

A: You collaborated with Google on this project. How did this come about?

BCW: I have done a few pieces with Google Arts and Culture in the past. I worked with an engineer called Bryce Cronkite-Ratcliff on a previous work of mine called Cold Flux. In 2021, he introduced me to a research scientist called Jason Baldridge who was developing AI image models at Google. We started discussing possible projects and how they might be interesting to artists. We picked up the conversation in 2025 again but this time the conversations led to a new artwork, involving the same ideas we were discussing in 2021, but with tools that could deliver the project in a way that felt even more compelling.

A: What initially drew you to self-portraiture as a topic for exploration?

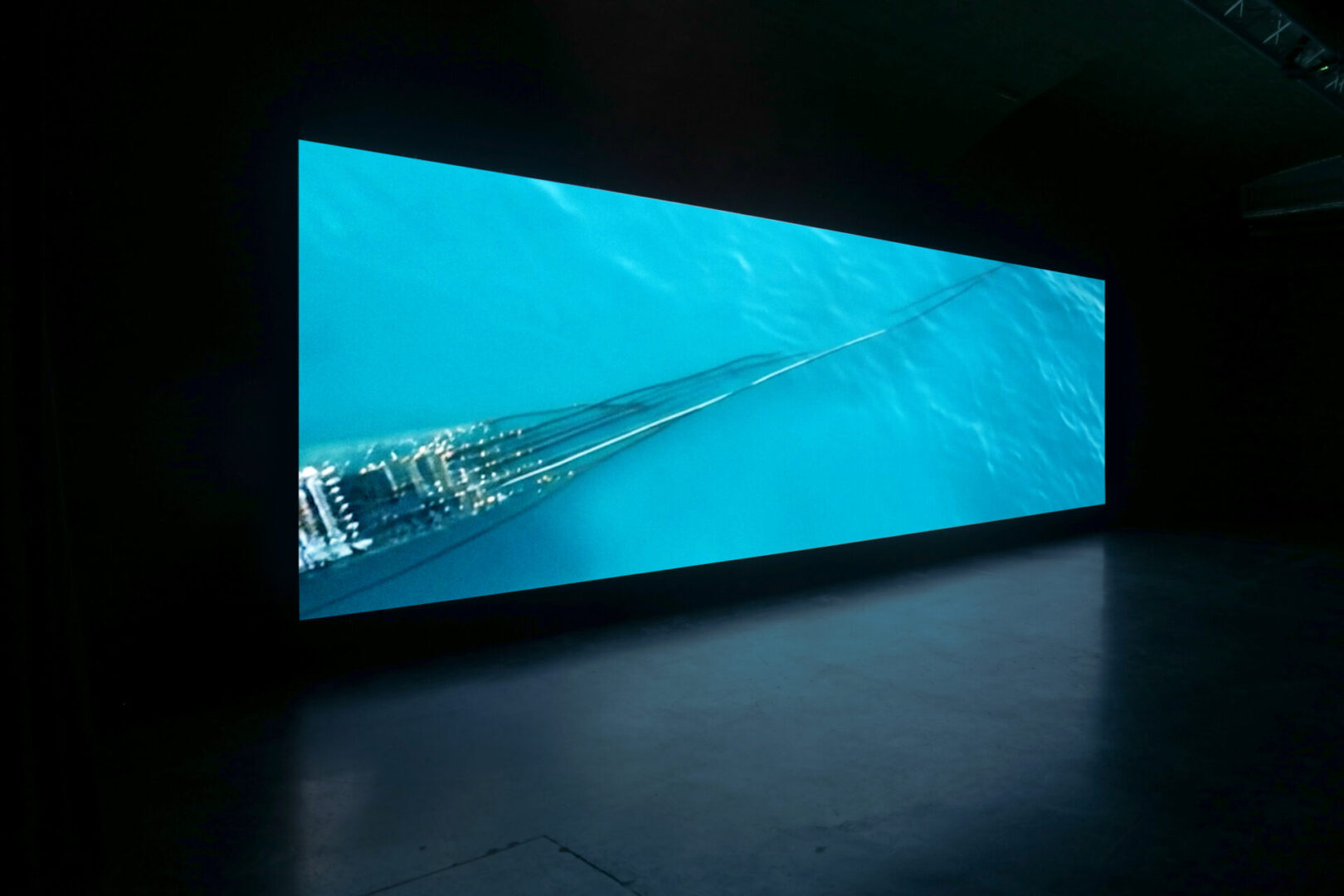

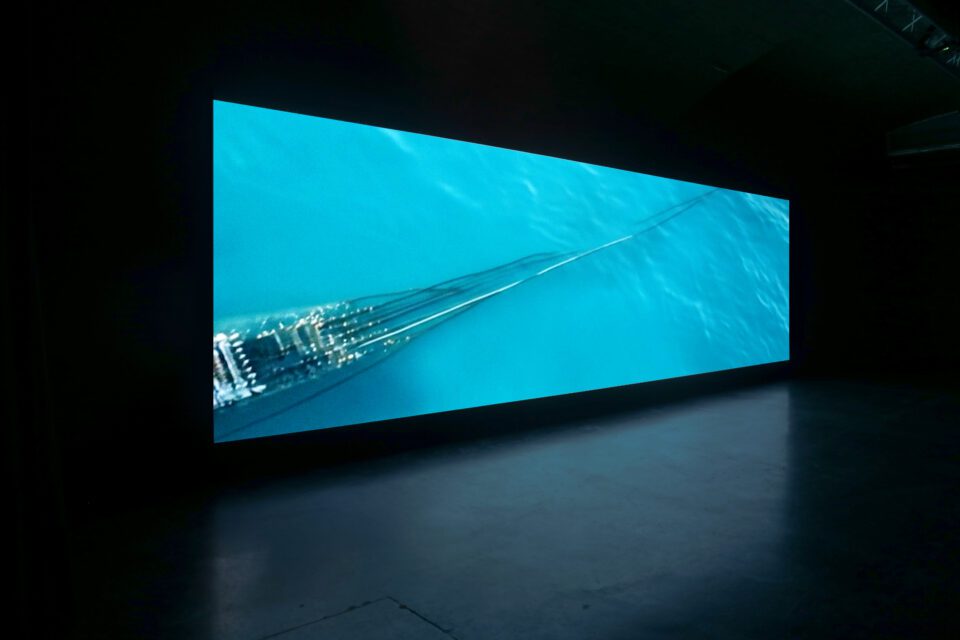

BCW: When Jason and I started discussing this in 2021, I was curious to know what the image model might know about itself. Would the it be able to reveal the complexities of its own system? At that point I wasn’t fully aware of how vast and industrial the generative AI network is, from huge networks of underwater cables, cooling towers, sprawling data centres. I started to get increasingly more interested in this, and the more we asked, the more it seemed like the AI was giving us a visual representation of itself. I hadn’t seen any attempts at a self-portrait by AI, so thought that there could be space for me to explore the subject.

A: Traditionally, a self-portrait is an act of human reflection. How do you interpret this concept when the “self“ is a machine?

BCW: Self is open to interpretation, is it a reflection of individualism or being part of a wider interconnected system? This question is one of the key issues I was grappling with in this project. Is this work a self-portrait by the AI at all? Or perhaps, as AI networks are a wide collection of human knowledge, rather than the singular “self,” is it the group that we are seeing?

A: Were there any moments in the process where AI surprised you?

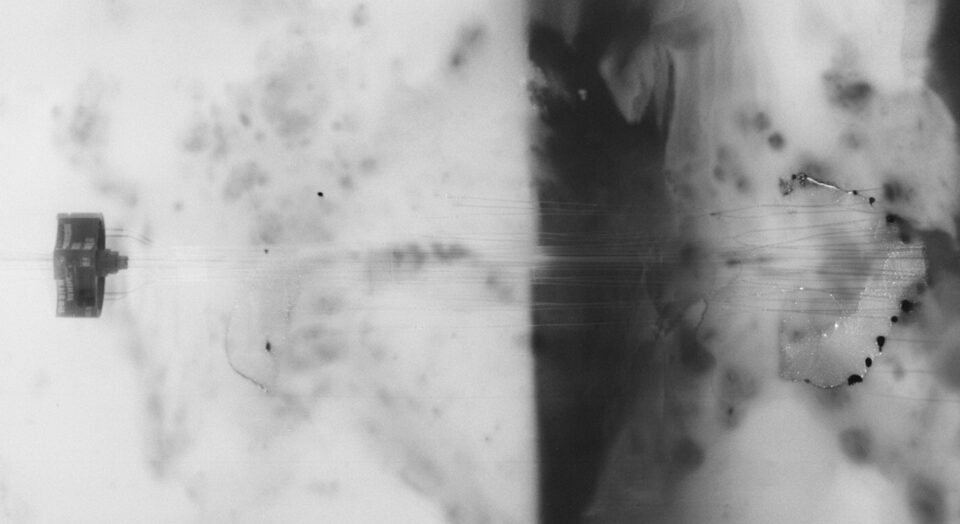

BCW: Through working with DeepMind, we were able to fine-tune a series of image models on my photographs. As a result, we were able to give the model an image prompt and it would generate an image that stylistically looked like I could have taken. This process created pieces that felt incredibly human, with flaws and imperfections. They were shots that I wasn’t aware that generative AI was able to make, since much of the AI images I had seen to date seemed quite glossy and similar in terms of aesthetic appearance.

A: How do you navigate authorship when collaborating with a machine?

BCW: When using any kind of technological medium that has its own rules, it’s really about navigating those to suit what you are trying to achieve. For example, within photography a certain type of digital camera will have very different outcomes to a film camera. You need to choose the model and the brand that suits what you are trying to do. Within this context, we need to choose what machine or tool is most appropriate for us. Within my work, I aim to question the subject with the medium itself so, for example, when using AI, I am actually questioning the medium of AI. This brings the tool deeper into the work, giving intention to my decisions. Alongside this, I generally modify the tool or machine that I am working with, such as using custom models or training data. If I’m creating photos, I work directly with the film negatives and often modify the camera. However, there is always an imprint of the machine or tool.

A: You’ve compared the process of making this work to being in a photographic darkroom. Can you tell us more about that?

BCW: When we began fine-tuning the AI image model we started with the default visual style. For example, if you ask the model to show you a building on a summer’s day, it will render that in a style that it considers appropriate for that prompt. We started exposing the image model to my photographs for varying lengths of time. We found that the longer the model was exposed to my photographs, the less it started looking like the default model style and more like the style of the photographs it was trained on. Through this process, we could affect the model in what felt quite a material way, in some way analogous to exposure in a darkroom or manipulating the photographic paper.

A: Do you view the work as a portrait of yourself, AI, or somewhere in between?

BCW: The work certainly sits in a grey area between the two: the subject is AI, the knowledge of itself comes from AI, the medium is AI. However, it has been trained on my photographs, I curated the prompts, I edited the film and worked with the composers and crucially the concept is mine. So the line is blurry – is it a self-portrait of my artistic practice or a self-portrait of the AI?

A: How do you see the relationship between artist and artificial intelligence developing in the future?

BCW: We need to continue to work with AI through projects that contain criticality, to form new understandings and thoughtful engagement with the rapidly developing technologies and create a useful and productive relationship between the arts and artificial intelligence. Ideally, it can be a positive point of friction, leading to unexpected outcomes, while also enabling more ambitious projects to be realised with less resources. However, there has always been a line between art and production, which fundamentally comes down to intention. Not all photographs taken on a camera phone are artworks, but it doesn’t stop a photograph taken on a camera phone from being an artwork.

A: Can you tell us about some of your other artworks?

BCW: I am currently redeveloping a work I created with Sir Wayne McGregor, which will be presented in an exhibition of his wider collaborative practice at Somerset House this winter. It’s a large-scale kinetic sculpture, on which a few films I have made with McGregor will be projected. At the same time, I am continuing an image and film based project I started a couple of years ago while on a residency at the base of Mount Etna while it was erupting. This culminated in an exhibition. The relationship to mountains and technological interventions through the documentation and recording will be developed in a second connected residency in the Dolomites at the start of 2026.

bencullenwilliams.net | @bencullenwilliams

Words: Emma Jacob & Ben Cullen Williams

Image Credits:

All Images Courtesy of Ben Cullen Williams.