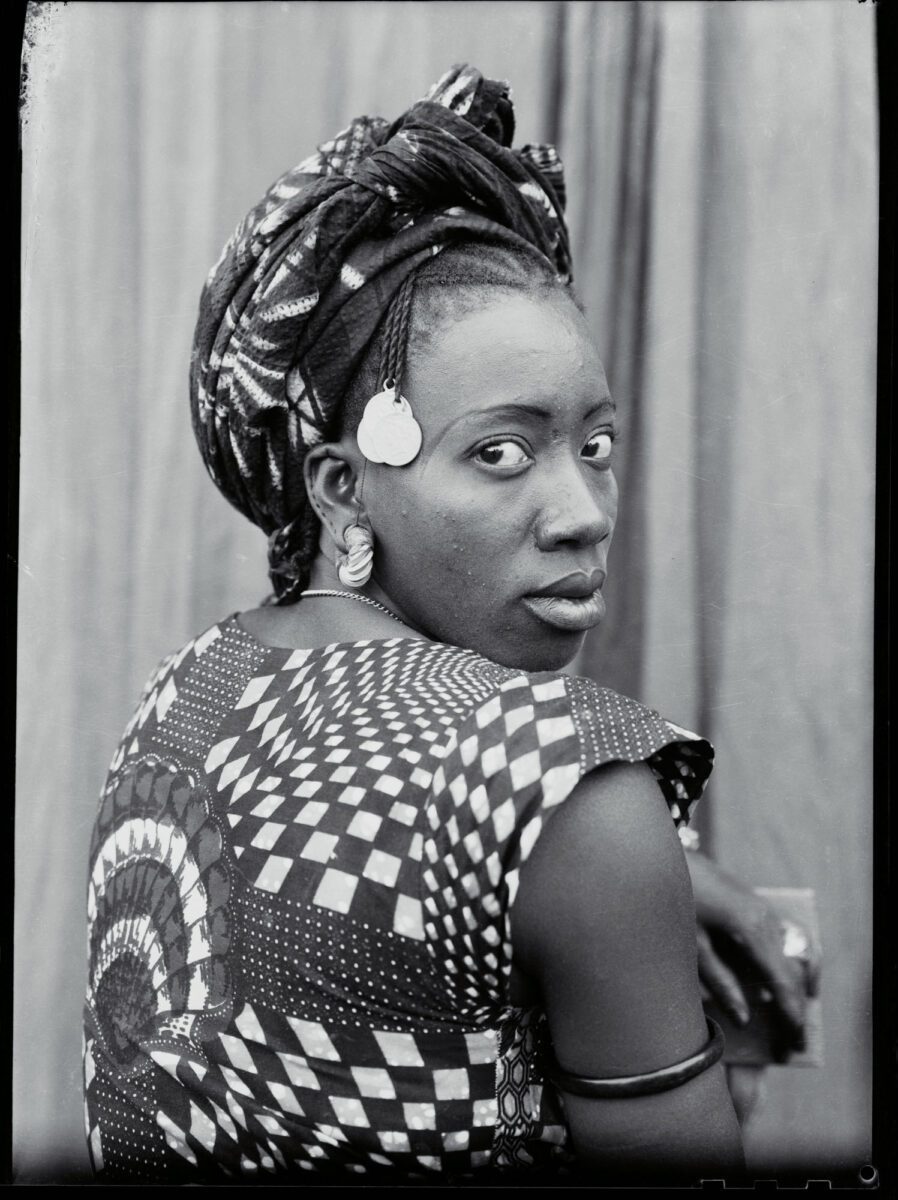

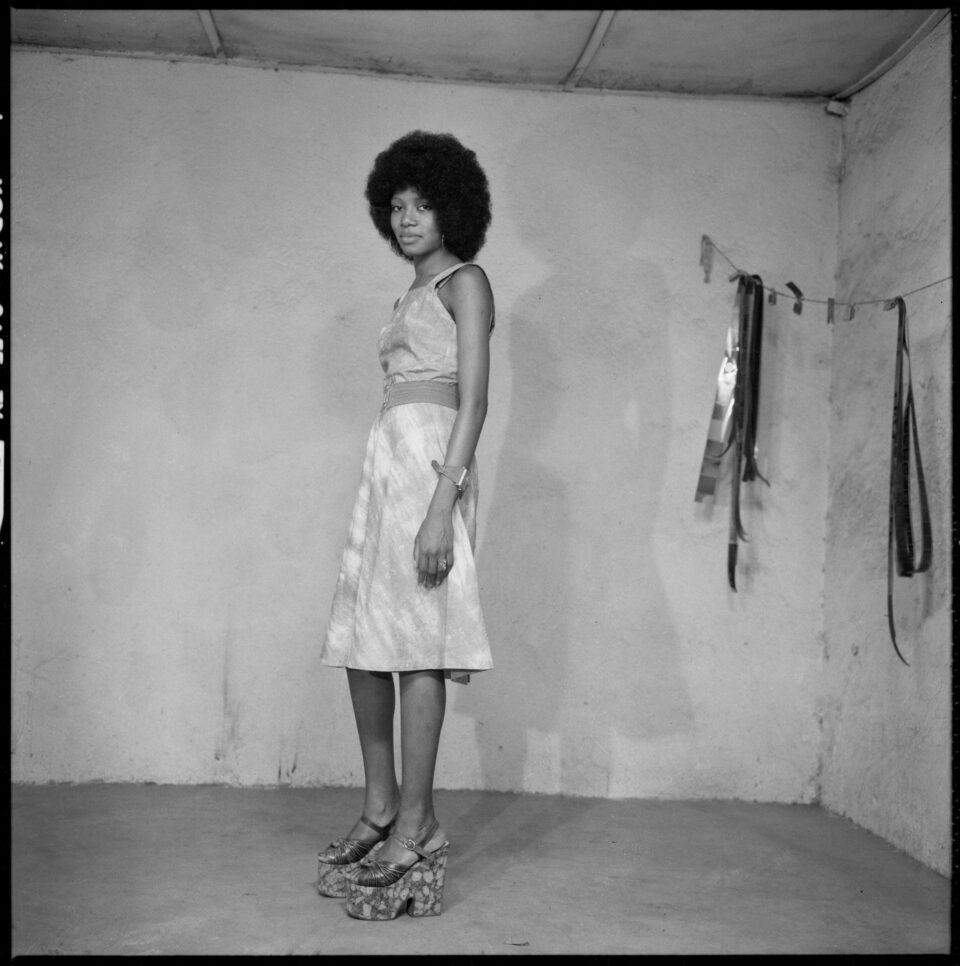

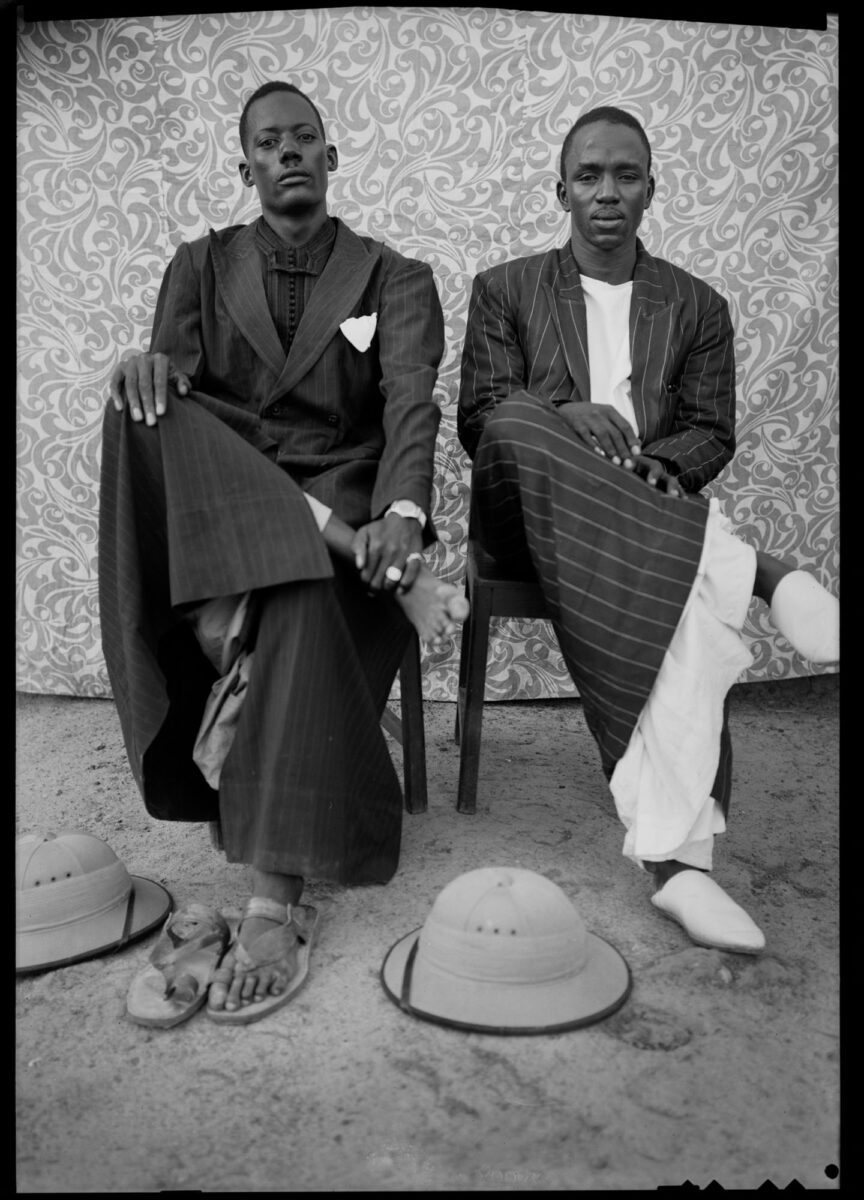

Seydou Keïta: A Tactile Lens opens with unmistakable force. The Brooklyn Museum draws visitors into the charged atmosphere of mid-century Bamako, where political transformation and personal aspiration met in the intimate space of a studio. More than 280 works build a world of surfaces and sensations, from elaborately patterned cloth to gleaming accessories and the quiet poise of sitters who understood the camera as a tool of self-realisation. Here, tactility becomes a crucial narrative thread, revealing how material choices shape identity in a moment of development and social change.

Keïta’s portraits were made during a period when Mali was moving towards independence and urban life was in rapid evolution. Bamako had become a place where young people experimented with modernity through clothing, gesture and ornament. Keïta captured this with a sensitivity that feels both formal and deeply collaborative. Guests arrived at his courtyard studio ready to craft their own image. He responded with an eye trained not just on composition but on the textures that defined a life. Catherine E McKinley, the curator, observes his “extraordinary artist’s ability to render the tactile” and the sense that viewers can “visually ‘finger the grain’ of the sitter’s lives.” It is this sensory immediacy that sets his work apart.

Within the broader history of photographic portraiture, Keïta sits in compelling dialogue with Ghanaian photographer James Barnor. Both were working at pivotal moments when West African cities were reshaping their identities and asserting new cultural agency. Barnor’s Ever Young studio in Accra shared Keïta’s ethos of allowing subjects to dictate their own presence. Each created a visual register of communities experiencing seismic social transformation. The energy of these decades, marked by ambition and the desire to be seen on one’s own terms, runs through their work.

Irving Penn provides another instructive parallel. Although their contexts differ, both artists understood the expressive power of the studio. Penn sought clarity through reduction. Keïta found it in visual richness. His portraits thrive on the interplay of patterns, the lustre of metal and the sculptural possibilities of pose. Yet both share a respect for the sitter’s self-fashioned identity. A contemporary resonance emerges in the work of Zanele Muholi, whose portraits assert presence with a decisive intensity. Muholi’s images echo Keïta’s belief in portraiture as a space of dignity and agency. Their sitters meet the lens with the same sureness and conviction that identity is something to be authored. It is here Keïta’s legacy feels most alive.

The impact of Keïta’s work on global visual culture is profound. When his photographs were first shown internationally in the early 1990s, they reframed expectations of African modernity and expanded the possibilities of studio portraiture. Designers still draw from his orchestrated patterns. Fashion photography continues to borrow his balance of poise and exuberance. Filmmakers and musicians reference the intimacy and confidence embedded in his intricate imagery.

However, the heart of A Tactile Lens lies in the reconstruction of the Bamako studio’s spirit. Keïta opened his space in Bamako-Coura in 1948 and quickly became known for welcoming a cross-section of Malian society. Urban professionals, villagers, families and travellers all stepped into the same environment. The exhibition captures this openness by pairing portraits with textiles, garments and jewellery from the period. A bracelet appears again in a vitrine. A printed cloth hangs nearby in its physical form. These pairings highlight how the aesthetics of the studio were anchored in the material culture of the city.

McKinley’s curatorial approach is grounded in intimacy and deep research. Working with Curatorial Assistant Imani Williford, she creates a sequence of galleries that build gradually from familiarity to revelation. Their design honours the nuance of Keïta’s practice without imposing narrative excess. Every detail feels considered, every object placed to illuminate the interplay between sitter, fabric and camera.The inclusion of never-before-published negatives, lent by the Keïta family, forms one of the exhibition’s most compelling elements. Some appear as glowing lightboxes, others as projections that animate the photographer’s sense of rhythm. Vintage prints, including hand-painted works made by Keïta himself, sit alongside later enlargements whose tonal range has become synonymous with his style. Rather than flatten these differences, the curators let them reflect the evolving contexts of his life and work.

A soundtrack by Nile Rodgers and Chmba Chilemba threads through the galleries. It evokes the pulse of a city in transition, heightening the sense of possibility that shaped Keïta’s studio. Pauline Vermare, the museum’s Phillip and Edith Leonian Curator of Photography, expresses the wish that visitors “feel the wonder and possibility that Keïta’s studio represented for so many people.”

Throughout the exhibition, a tension unfolds between the practical and the aspirational. Many sitters came to Keïta for straightforward reasons, yet the images they left with often carried a deeper charge. These portraits reveal the optimism of a society shaping its future through pose, material and intention. They are artefacts of self-invention at a moment when identity was both personal and political. By the time visitors return to the opening rooms, the portraits have deepened. What first appeared as individual encounters becomes a collective portrait of a society learning to see itself anew. McKinley’s emphasis on tactility allows viewers to understand how texture and form shape personal agency.

Ultimately Seydou Keïta: A Tactile Lens is an act of restoration. Through sensitive curation and the unveiling of new works, the Brooklyn Museum brings Keïta’s studio back into vivid presence. His portraits remind us that cultural transformation often begins in small rooms where individuals stand before a camera not only to be recorded but to assert who they are and who they imagine themselves becoming.

Seydou Keïta: A Tactile Lens is at the Brooklyn Museum until 17 May.

Words: Shirley Stevenson

Image Credits:

1. Seydou Keïta. Untitled, 1949–51, printed ca. 1994–2001. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the Musée national du Mali. © SKPEAC/Seydou Keïta, courtesy The Jean Pigozzi Collection of African Art and Danziger Gallery, NY

2. Seydou Keïta. Untitled, 1952–55, printed 1994. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of The Jean Pigozzi African Art Collection. © SKPEAC/Seydou Keïta, courtesy The Jean Pigozzi Collection of African Art and Danziger Gallery, NY

3. Seydou Keïta. Untitled, late 1940s to mid-1970s. Positive reproduction from digitized negative. Courtesy of the Seydou Keïta Family

4. Seydou Keïta. Untitled, 1956–57, printed 1994. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of The Jean Pigozzi African Art Collection. © SKPEAC/Seydou Keïta, courtesy The Jean Pigozzi Collection of African Art and Danziger Gallery, NY

5. Seydou Keïta. Untitled, 1949–51, printed ca. 1994–2001. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy of the Musée national du Mali. © SKPEAC/Seydou Keïta, courtesy The Jean Pigozzi Collection of African Art and Danziger Gallery, NY