“You catch more flies with honey than vinegar.” It’s an adage that dates back to 1666, and today, is used in households across the world. It means that if you’re trying to win someone over, being kind and pleasant is more effective than being harsh or aggressive. The phrase is also the inspiration beind a new exhibition at Whitechapel Gallery, London. Joy Gregory: Catching Flies with Honey is a landmark show that brings together 250 works encompassing photography, film, installation and textiles. The title encapsulates Gregory’s approach to art as “political with a small p”: her intimate, visually pleasurable and poetic works encourage nuanced, rather than polemical, discussions. The artist is one of the UK’s most innovative creatives, and since the early 1980s, she has pioneered new techniques and approaches in contemporary photography. Her work explores identity, race, history, gender and societal ideals of beauty, often challenging expectations of how Black or feminist art “should” look. Whitechapel’s show is the first major survey of Gregory’s artwork, presenting audiences with a unique chance to traverse her forty-year career. Aesthetica caught up with the artist ahead of the show’s opening, to chat about her practice, how her creative approach has progressed over time and how she hopes to engage with audiences.

A: This is the first major survey of your work to date. What was it like to look back at your career?

JG: I’m one of those artists that never really looks back, I’m always moving onto the next project. One of the great things about curating this show was being able to see how different creative threads have come together. There are things that you’d think were completely disconnected that actually have a lot in common. For example, you may not see Memory and Skin as having much to do with Girl Thing, but then you realise that the empty clothes or objects that are documented in Girl Thing are actually about the body and how it’s used as a cipher for political thought, like I explore in Memory and Skin. When I was making them, I wasn’t thinking about reflecting everything that was going on around me, but looking back, you realise that you can’t help but be influenced by the things you hear and how you feel in response to them.

A: You’ve been a driving force in photography since the 1980s. Has your approach changed over time?

JG: It’s become more confident. Technology has changed in so many ways but I still primarily work in analogue, although I do use digital occasionally. One real shift has been in the fact that I have access to so many materials without having to leave my home. Now, I can do my fact-checking from the studio rather than having to fly back to Johannesburg or Yale. In the early days, I couldn’t do that. When I was making Memory and Skin, which was one of my first installations, the premise was to look at the connections between Europe and the Caribbean. I remember I had plans to go off to Cuba and travel about the Caribbean on my own with just a rucksack and my Hasselblad and a sound recorder – I was met with absolute horror by everyone I told. You didn’t know anyone and couldn’t get in touch with people in advance via the Internet. It was essentially like you’d jumped off a cliff, and nobody would hear from you for months, and then you’d come back. There was also the assumption that people wouldn’t speak your language, and you’d move around and meet different people and interview them, without really knowing what the outcome would be. Today, you’d be able to call someone up on Zoom and have these conversations without having to travel to be with them physically.

A: The exhibition’s title comes from the saying “you catch more flies with honey than vinegar.” Tell us about what this phrase means to you, and why you chose to it as the name of the show?

JG: My mother used to say that a lot, meaning that if you wanted to get something done, rather than going in gung-ho and putting people off by saying “this is the way it should be,” you make it more appealing. My work is quite beautiful and I’m not ashamed of that. At first, I was a bit worried that I’d be perceived in a certain way because of it. Now, I think that if you want people to listen to you and take an interest in what you have to say, you need to make it palatable. That way, they’re far more likely to be curious. They might not want to engage with it, or take the idea on at all, but at least they’ll look at it. Whereas if you create something that’s more confronting, not only will people not agree with it, but they won’t consider it at all. It’s about having a more appealing way to bring people to the table.

A: Your work often examines power, representation, identity and cultural memory, and you’ve collaborated with communities worldwide – including in the Caribbean and with the San People in South Africa’s Kalahari Desert – to do so. How have these experiences informed your practice?

JG: Trust is the most important part of a collaboration. For many of those I’ve worked with, trust has been abused over many years. It takes a long time to build. We did this through going back to the same location time and again. We also went into archives at different universities to look at the history of how groups like the San People have been misrepresented. Projects become 10 times richer when you join forces.

A: Can you yell us about your investigation into language – or, more specifically, the loss of language?

JG: I initially started looking into language as part of my Nestor fellowship. The first project I did was about the endangered language of Silbo Gomero, which is from the island of La Gomera. It was once almost lost, but it’s been protected and revived, and now it’s taught in schools. Later, when I was exploring the same concept in the Caribbean, one of the places I went to was Panama. There’s a community in Panama City who speak English. This was really curious to me because they identify themselves as being different from the people of African descent who moved to Panama after emancipation in the Caribbean islands. They’ve held onto this very Victorian English, and talking to them, they’re very proud of the fact that they speak the language, even though it’s completely frozen and very different to how it sounds in other parts of the world. The conversations I had just really stuck with me because there were a community who ended up in Panama because of the canal, which was being built by English-speaking Americans, so they saw no benefit in learning Spanish. Language is completely wrapped up in history and politics.

A: Let’s talk about beauty. It’s a topic that comes up a lot in your work, in series like Autoportrait, Objects of Beauty and The Blonde. Why do you return to this concept?

JG: Objects of Beauty was about the fact that women were taking up so little space. I documented items that were associated with being beautiful and the equipment or products people use to make themselves more attractive. These things become curiosities when you put them in isolation. One that sticks out is the corset, which is something that physically restrains you, makes you take up less space in the pursuit of beauty. The whole idea becomes absurd once you look at it from another angle. In terms of Autoportrait, that was really about the absence of people who looked like me, or the way these people were presented back when I was growing up. It’s about erasure and highlighting who has been erased.

A: In Girl Thing, silk bras, corsets and handkerchiefs are presented as cyanotypes. Why this technique?

JG: I studied at the University of Manchester and at that time, there were only three or four photography courses at a degree level. I chose that one because they had a photo science component. I’ve always found it very difficult to choose things, and at the time I was torn between art, social sciences and science, and this felt like it combined all of those things together. I was interested in knowing how the material worked. I took everything out of the library and tried every technique I could – from potato prints to making my own colours. I was just really curious and that inquisitiveness is something that still drives my work. There was something about seeing the scientific practice of people like Anna Atkins or John Herschel and then putting it into practice that I really liked. I don’t like to use materials properly, I like to try and abuse things and push them to make them do things that shouldn’t really do.

A: Do you have a particular work or series that stands out to you as a favourite?

JG: I almost feel like all of it is one big work, in a sense, because with each one builds on the previous. It’s like I’ve been working on the same thing over and over again. There’s been a lot of failures and things that haven’t worked, which are just as important because they’re a lesson.

A: What do you hope visitors take away from visiting the Whitechapel show?

JG: I’m always surprised when people engage with my work in the way that they often do. I remember when I showed Memory and Skin in Bath at the Royal Photographic Society. It was around that time that I had a got in touch with an agent, and I really thought that I wouldn’t even see me, but they invited me in. At the meeting, the agent said he’d seen my work and thought it was really beautiful and he pointed out that it didn’t make him feel like he was to blame for anything. It was interesting to hear because I try and make it so that my work isn’t about finger pointing, it’s about bringing issues to light. I think that’s important. I don’t want to make you take on my point of view, but I’d like you to engage with it.

Joy Gregory: Catching Flies with Honey is at Whitechapel Gallery, London until 1 March 2026: whitechapelgallery.org

Words: Emma Jacob & Joy Gregory

Image Credits:

1. Joy Gregory, Kalahari (Magdalena Runs) 2005–2010 C-type print © Joy Gregory.

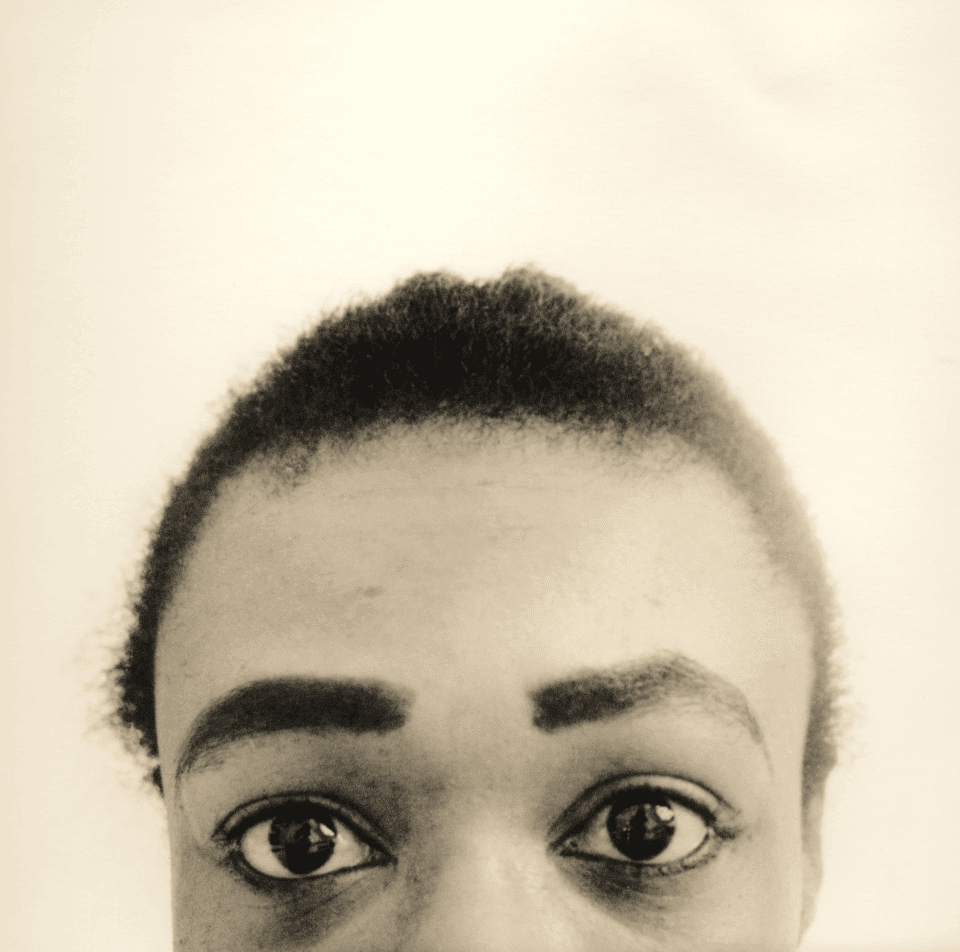

2. Joy Gregory, Autoportrait 1989–1990. Silver Gelatin Lith Print © Joy Gregory / Courtesy the artist & DACS.

3. Joy Gregory, Cadiz from the series ‘Cinderella Tours Europe’ 1997–2001. Fuji Crystal Archive Print © Joy Gregory.

4. Joy Gregory, Autoportrait, 1989–1990. Silver Gelatin Lith Prin t© Joy Gregory / Courtesy the artist & DACS.

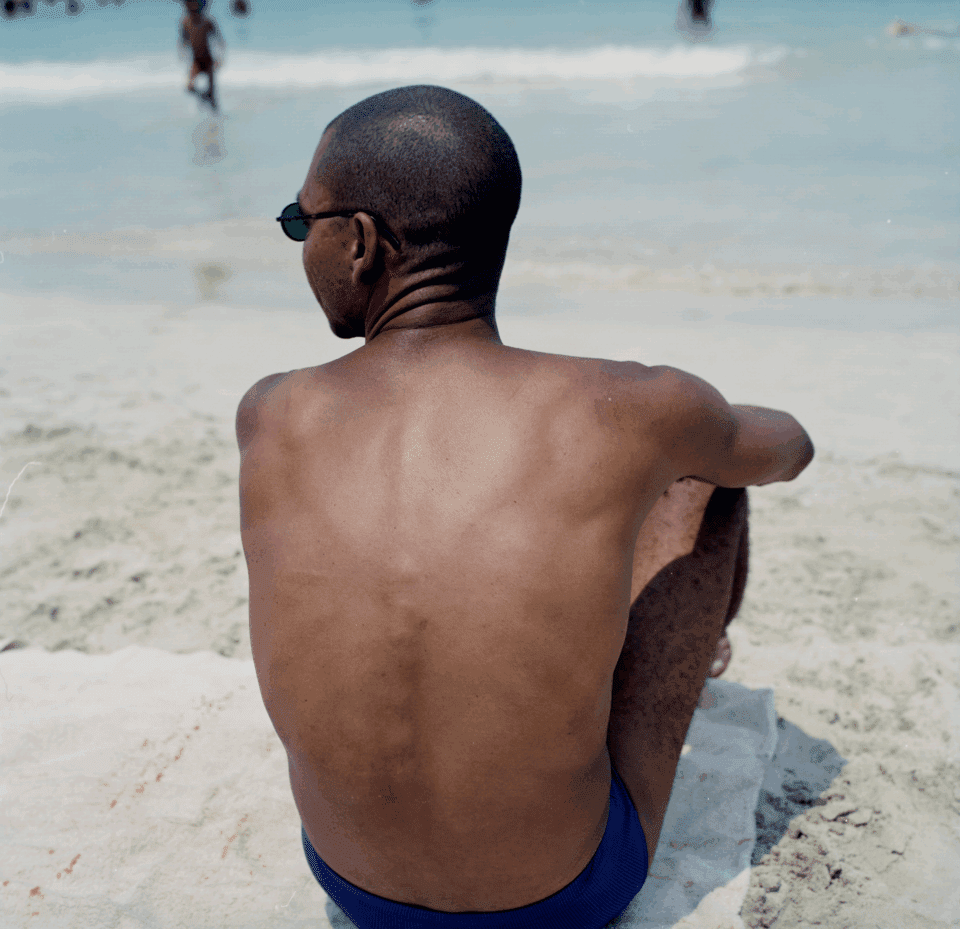

5. Joy Gregory, Manuel Pina (Portraits – from ‘Memory and Skin’) 1998 C-Type Print © Joy Gregory.