The term “Artificial Intelligence” was coined by John McCarthy in 1956, marking the formal beginning of AI as a field of research. It was an area that would boom over the latter half the 20th century, beginning with simple machine reasoning games like chess. Today, millions of people have this technology in their homes – think Alexa, or Siri. Perhaps the most significant development in recent years, however, is the emergence of ChatGPT. The generative model was released onto the market in November 2022 and today, it is report that more than 200 million people use it each week. Yet for all its convenience, artificial intelligence has also brought with it serious concerns about creative integrity, intellectual property and job opportunities. The Guardian recently published an article titled Will AI Wipe Out the First Rung of the Career Ladder?, whilst the UK Government came under immense fire for its plans to allow tech companies to use copyrighted material to train their software. Artificial Intelligence is one of the defining issues of the modern day, and the debate does not look set to stop any time soon. Jeu de Peume presents a selection of artistic works that raise questions around how we experience the world “through the prism of AI.” It features works created between 2016 and today by more than 30 world renowned artists, including Julian Charrière and Hito Steyerl. The exhibition seeks to expand the narrative around the technology, considering its possibilities as well as its potential pitfalls. Aesthetica spoke to Assistant Curator Ada Akerman about the show, why it is important to tell a nuanced story, and what she hopes audiences will take away from the experience.

A: The World According to AI is the first exhibition of its scale to interrogate artificial intelligence through a contemporary art lens. How did the concept for this ambitious project take shape?

AA: The show came from two research projects: CulturIA. For a Cultural History of AI, directed by Alexandre Gefen, and Antonio Somaini’s AI’s impacts on Visual Culture. We wanted to offer an insight of what it means today, in terms of visual culture, to look at the world throughAI. The show is a collection of various approaches and ideas by artists to situate themselves within a new cultural zeitgeist. We also aimed to unveil what AI really is by selecting works which deconstruct problems with the technology, and that also highlight its overlooked and not so well-known dimensions. At a time when the subject matter is wrapped up in highly political, geopolitical, economical, social, epistemological debates, it seemed necessary to debunk some mythologies and discourses. The exhibition is divided into two main sections, following Jeu de Paume’s architecture; the first one is dedicated to analytical AI, the second to generative models.

A: The exhibition opens with works by artists like Julian Charrière, who uses natural objects like rocks to map the material and environmental aspects of AI, and examine its ecological impact. Why was it important to begin here?

AA: One of the first gestures to open the “black box”, so to say, is to remind audiences that the technology is material. Many discourses, especially those coming from the major companies developing AI, enhance its so-called dematerialisation: the “cloud” ideology. Deconstructing these perceptions seemed like the perfect way to start the show. We also wanted to surprise the viewer, as they probably would not expect an exhibition dedicated to AI to begin with a mineralogical gallery. It was important for us to foreground sculpture, with its three dimensionality, because people don’t really think of AI in terms of tangible objects. It’s a way to ground the discourse in a material perspective.

A: What surprised you most during the curatorial process – about AI, the artworks, or public perception?

AA: AI technologies, and their applications, are evolving at a steady pace. It was a challenge to build a show about a constantly changing landscape and in such pivotal times. I have been surprised by the diversity of artistic approaches to the subject matter. Unfortunately, images associated with these technologies are often kitschy and entertainining, and are too often the subject of shows dealing with AI. The works in The World According to AI cannot be reduced to the label of “AI art”: many artists exhibited in the show use AI among an array of various artistic mediums.

A: What does AI mean for creativity today? Can machines really co-create with artists?

AA: AI systems and models – be they analytical or generative – can provide artists with new creative gestures and material. However, it is important to remember that convincing works can never be made only by the machine. They always require many human interventions, in a constant process of back-and-forth. This implies various strategies from artists: creating their own generative models, feeding them with a selected training corpus, or personalising them through different operations and tools. In the case of “text-to-image” and “text-to-video”, it becomes extremely important to master the art of prompting – to become a prompt engineer, so to say – in order to get a satisfactory result. Generative AIs can become extensions of the artist: creative alter egos, conveying surprise, estrangement and awe. In our show, we have stepped away from futuristic aesthetics and attitudes. Instead, we favour artistic endeavours which rely upon generative AI in order to rework our cultural past, complete its fragmented artefacts and give life to aborted and unfinished art projects of the past.

A: Do you have a particular favourite work of art in the show?

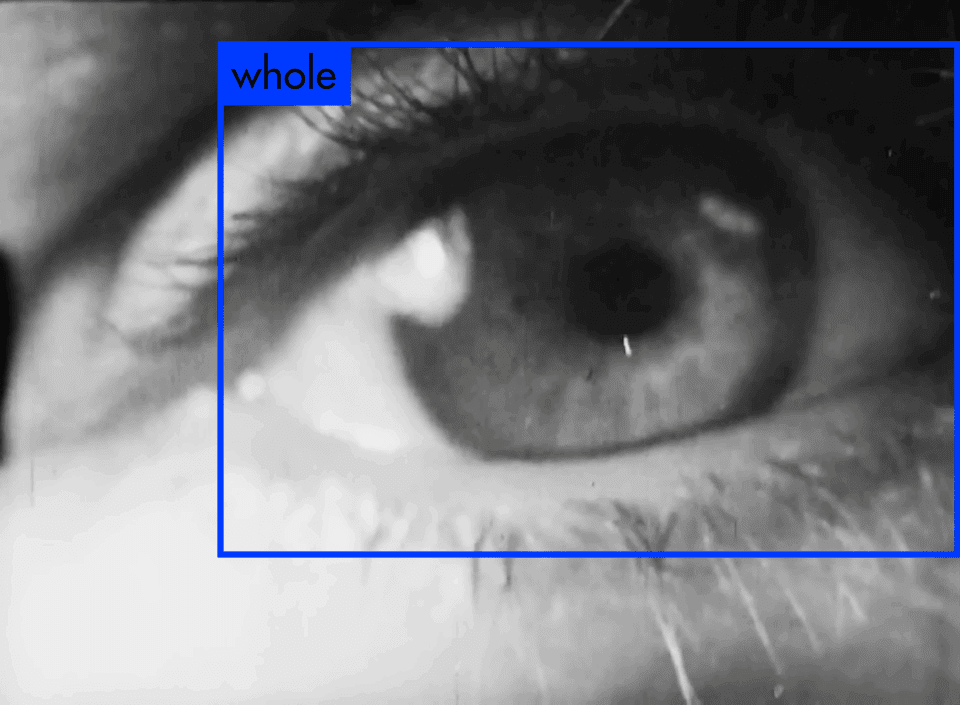

AA: It’s a hard question as so many exert a sheer fascination and gain new meanings each time I look at them. I am especially fond of Nouf Aljowaysir’s photographic series Salaf. Her haunting and troubling emptied silhouettes symbolise the limitations and failures of data collection and AI tools in collecting and interpreting Middle Eastern identity. I could also spend hours watching Hito Steyerl’s Mechanical Kurds, an audiovisual installation presented for the first time in our show. It is a documentary investigation into “click workers”, who operate from refugee camps in Kurdistan labelling and tagging datasets. Mechanical Kurds sheds light on how AI technologies can be exploited in conflict zones, particularly in the Middle East. Viewers sit on coloured benches and chairs that are reminiscent of analytical bounding boxes – the rectangular or square markers drawn around objects in images to help computers identify them. It reminds audiences that we are all subjected to automatic recognition and analysis, whilst raising awareness of working conditions of those employed by Amazon Mechanical Turk.

A: The World According to AI arrives at a moment of heightened public discourse around machine learning and automation. What do you hope this exhibition contributes to the cultural imagination around AI, beyond the museum walls?

AA: These technologies are never neutral nor mere tools – as, unfortunately, the uses of AI by extreme right wing parties demonstrate. But their uses shape our present and future world. They do this materially, as they need many natural resources, but also ideologically and philosophically, as AI models filter, transform, map, orientate and sometimes distort our understandings, perceptions and images of the world. A better understanding of their inner workings is needed in order to feel less subjugated by them. At the same time, we hope to demonstrate the richness and artistic potentialities of AI, and to suggest the incredible variety of new artistic gestures which can occur when creatives master these tools.

The World According to AI is at Jeu de Paume, Paris until 21 September: jeudepaume.com

Words: Emma Jacob & Ada Akerman

Image Credits:

Gregory Chatonsky, la quatrième mémoire, 2025.

Le Féral 2024-2025.

Christian Marclay, The Organ.

Estampa, What do you see YOLO9000, 2019.