Of the many counter movements that emerged out of the late 1960s and 1970s, Institutional Critique is, perhaps, one of the least widely discussed. It stood up against the traditional idea of the “art institution,” with creatives directly responding to the museums and galleries acquiring and exhibiting their work. Other institutional actors were put under the microscope, too, like financial firms, realtors and states. One pioneer was the German-born artist Hans Haacke (b. 1936), particularly for his work Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, a Real-Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971, which brought the economic ties between real estate and art collectors under scrutiny. Art in America recently remembered it as “Part journalistic exposé, part conceptual artwork.”

Today, with social media and round-the-clock news cycles, the expectation that the public can hold organisations to account has become somewhat of a norm. A quick Google search will yield articles that offer thoughtful, well- researched assessments of institutional strategies, from curation to acquisitions to funding sources, political stances and more, stoking industry-wide debate and sometimes even economic shifts. One recent example is the scandal surrounding the National Galleries of Scotland’s ties with controversial investment firm Baillie Gifford, or last year’s back- lash towards the British Museum for accepting funding from fossil fuel firm BP. These kinds of conversations date back to the mid-to-late 20th century. Not only was critique becoming method, medium and movement, but there were all sorts of ripples taking place that changed our perception of “art.” Conceptualism, for one, was fast becoming the movement du jour. There was a rise in performance-led practice. It was a time of questioning: artistically, creatively, politically. The parameters of where art could be accessed, and how, shifted. Even the very term “exhibition” gained a brand new meaning.

Against this backdrop, a young Welsh man, the son of a well-known photographer and painter, was pursuing his studies. Cerith Wyn Evans, born in 1958 in Llanelli, Wales, had been captivated by art from a very young age, having read British abstract artist Patrick Heron’s book The Changing Forms of Art by 11, and getting his local library to import Studio International and Flash Art for him, as he told The Art Newspaper in 2017. The young Evans completed a foundation year at Dyfed College of Art before attending Saint Martin’s School of Art (1977-1980) and the Royal College of Art (1981-1984) in London. Whilst in the capital, he worked as an invigilator at Tate, gaining knowledge of its collection.

Over the years, Evans has cultivated a practice where no typical day in the studio exists, nor any marriage to a particular approach. “I’ve never found it particularly constructive to make a distinction based on medium [anyway],” he shares. One of Evans’ teachers was notable conceptualist John Stezaker, whose work leaned towards the surreal, as well as theoretician and filmmaker Peter Gidal. Under their tutelage, Evans began to hone an artistic identity. Most significantly, he became assistant to the influential director Derek Jarman; with him, he worked on the films The Angelic Conversation (1985), Caravaggio (1986) and The Last of England (1987), as well as music videos for prominent bands like The Smiths.

Evans was embedded in London’s 1980s alternative scene; he was a squatter for a time and was studying, mixing, making and living as an experimental artist and filmmaker in a fertile creative period for the city. He collaborated with key figures such as dancer and choreographer Michael Clark, performer Leigh Bowery and the Neo Naturist group, whilst producing his own “non-narrative” videos. But he really emerged as a one-to-watch from the 1990s onwards, when he pivoted to- wards sculpture and installation. Despite the change of direction, his new work still incorporated light, sight and sound – fundamentals seemingly carried over from film. “I’ve chosen, over the years, to avoid ‘describing’ my work. It seems to undermine the very purpose of making it. For that reason, I’m privileged to afford a changing focus as feels right,” he says.

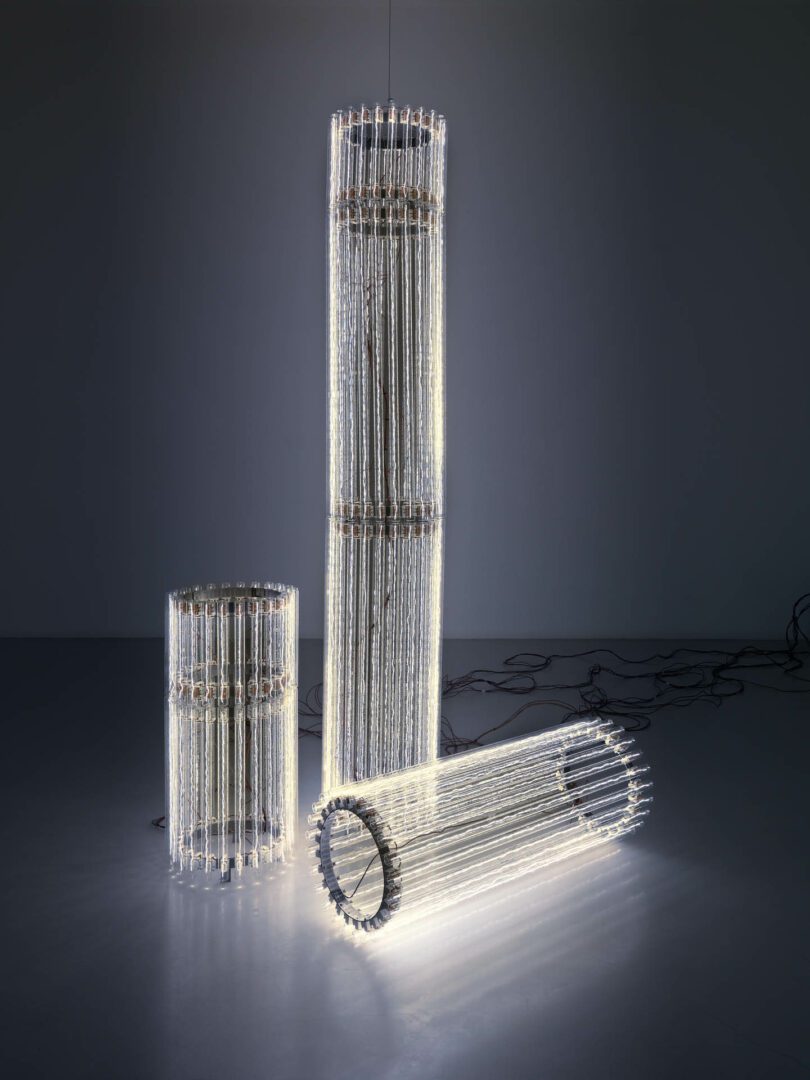

More recently, Evans presented ….the Illuminating Gas (2020) at Pirelli HangarBicocca in Milan, a former car factory. Evans installed 24 works from across his career, using the space to arrange them in such a way as to create dynamic harmonies between the art – their sights, lights and sounds – and its surroundings. It was bespokely curated and highly choreographed, making the show itself a meta, umbrella conceptual piece. Evans described it as a “love letter to the space.” “The context of a particular architecture plays a large part in my decision-making process,” he explains. In Milan, his first neon sculpture TIX3 (1994) was on show, as was his renowned 2017 Tate Britain commission Forms in Space… by Light (in Time), comprising several kilometres of neon tubes hanging from the ceiling in a complex, explosive shape. It is influenced by kata diagrams from Japanese Noh theatre, which also inspired the 2015-2019 sculpture series Neon Forms (after Noh). Other parts of Forms in Space… are mod- elled after musical notation, and LSD’s molecular formula.

Evans’ latest exhibition, his first solo in France since 2006, is Borrowed Light Through Metz at the Centre Pompidou Metz. His older works, from the past 10-15 years, meet more recent ones “in concert … the exhibition constantly mutates as if animated by an inner life.” The result calls into question the protocols of exhibition-making, and includes a “winter garden” of pieces in dialogue with the space’s existing Shigeru Ban-designed folding architecture. The Pritzker Prize- winner worked in collaboration with Jean de Gastines to craft the space back in 2010. Now, Evans fills it with big amethyst geodes and a bevy of plants from which two columns, made of filament light tubes, rise. They pay homage to the life-saving paper tubes Ban is known for, whilst signalling the evolu- tion of time towards an increasing reliance on technology. Conversely, the third floor gallery is a “stroll garden”, with walls covered in mirrors and large windows bringing the city of Metz into the installation. There are more columns, this time LED, plus glass sculptures and crystal flutes emitting sounds – a symphony of flickering, fading, calling, dancing and singing performed by everything but human beings.

Words Vamika Sinha

Borrowed Light, Centre Pompidou Metz | 1 November – 14 April

Image Credits:

Cerith Wyn Evans, ….the Illuminating Gas, Pirelli Hangar Bicocca, Milan. 31 October 2019 – 6 July 2020 © Cerith Wyn Evans. Photo © Agostino Osio. Courtesy of the artist; White Cube; Pirelli Hangar Bicocca