The Museum of Contemporary African Art seems to have a life of its own as it evolves one object, one room and one location at a time: although the work is infused with Gaba’s presence as the devoted collector and creator, the work nonetheless possesses the autonomy from authorship that any fine museum collection should.

The striking thing about Gaba’s work is that it sits in a liminal space between a museum collection of artefacts and a piece of conceptual art. The categorisation of rooms instantly gives the feeling that you are entering a very precisely curated museum collection. But with some individual pieces, such as the Artist’s Bank (1997 – 2002), a glass-topped writing desk that displays banknotes with architectural designs, it is only the familiar stark white walls of the gallery that reminds us that this desk is an artwork in its own right and not a piece of furniture of purely anthropological interest.

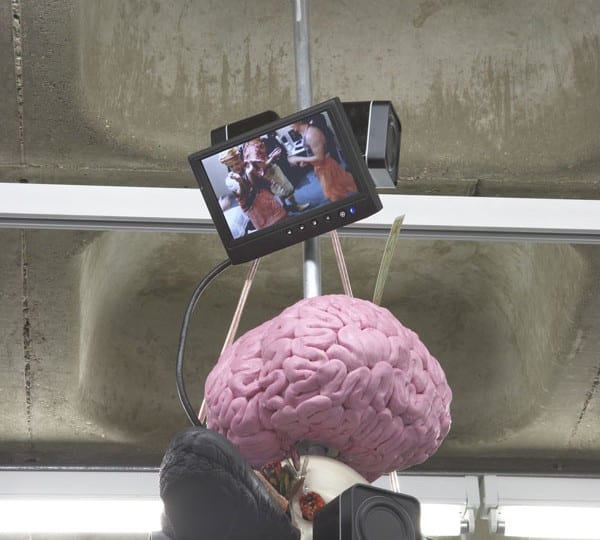

The Museum as a whole, as well as its individual components, plays on this uncertainty. On the one hand, by appearing as conceptual art, it creates a Brechtian distance between artefact and audience, providing a space in which to contemplate the emotional, cultural, personal and history significance of the work. But on the other, it involves interactivity, such as the luscious Salon Room where guests are encouraged to relax on the sofa, eat chocolates and play the piano; or the building blocks in the Architecture Room where guests are invited to design a permanent home for the Museum.

Gaba makes some strong political statements with such aesthetic flourish that they never quite become the locus of the work. In the first room, bread rolls and chicken legs have been cast in clay and painted glittering gold to highlight the grotesque disparity in food poverty between Africa and Europe. The Marriage Room is so personal, containing photos of his own wedding and his wife’s actual wedding dress, that you almost miss the heartfelt lament for the dying respect for marriage in the modern world.

Although each themed section of the Museum is called a ‘room’, there is no sharp division between, say, the Game Room and the Salon, and the Music Room bleeds uncomfortably into the Museum Shop. This lack of a spatial distinction between interactive and contemplative parts often does not work in the booming, over lit, bustling corridor galleries of Tate Modern. Gaba has a lot to say, but in this arrangement it is sometimes difficult to hear him.

The most striking recurring motif is that of the banknote, which appears again and again as a critique of economic policy and inequality. Throughout the Museum, pianos, tables and chairs are adorned with little circles that have been cut out of banknotes, as if the marginalisation or misunderstanding of African art can be aptly expressed by this brash appropriation of Hirst’s own spot motif. Gaba, you quickly realise, has a fine sense of humour and an even greater love of humanity, making his Museum both a cultural delight and an important move towards redressing a long ignored imbalance.

Meschac Gaba: Museum of Contemporary African Art, 3 July until 22 September, Tate Modern, Bankside, London, SE1 9TG. www.tate.org.uk

Credits:

1. Museum of Contemporary African Art 1997 – 2002 (Salon), Kunsthalle Fridericianum. Photo: Nils Klinger. © Meschac Gaba

2. Museum of Contemporary African Art 1997 – 2002, Centro Atlantiko de Arte Moderno, © Meschac Gaba